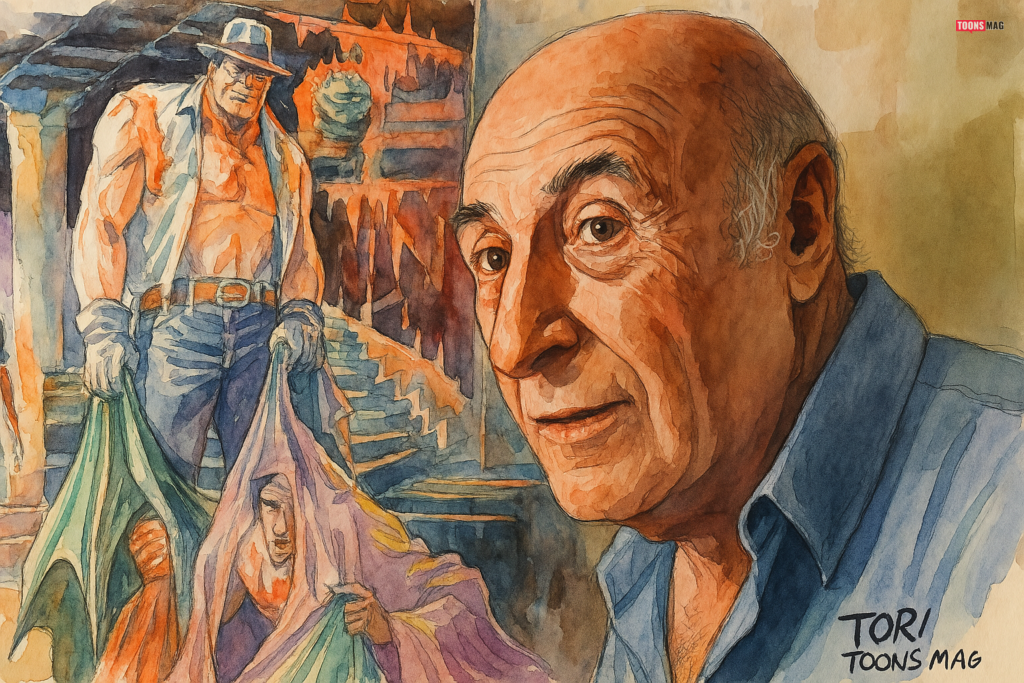

William Erwin Eisner (March 6, 1917 – January 3, 2005) was a groundbreaking American cartoonist, writer, and entrepreneur. Widely recognized as one of the most influential figures in the comic book industry, Eisner’s innovations helped shape the art form in both content and format. He is best known for creating The Spirit (1940–1952), one of the earliest comic book series to experiment with cinematic storytelling, and for popularizing the term “graphic novel” with the publication of A Contract with God in 1978. A visionary thinker, Eisner also authored the landmark instructional books Comics and Sequential Art and Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative, laying the groundwork for comics studies as a serious academic discipline.

Infobox: Will Eisner

| Full Name | William Erwin Eisner |

|---|---|

| Born | March 6, 1917, New York City, U.S. |

| Died | January 3, 2005 (aged 87), Lauderdale Lakes, Florida |

| Occupation | Cartoonist, Writer, Publisher, Educator |

| Nationality | American |

| Notable Works | The Spirit, A Contract with God, Comics and Sequential Art |

| Spouse | Ann Weingarten Eisner |

| Children | John Eisner |

| Years Active | 1936–2005 |

| Awards | Reuben Award, Inkpot Award, Grand Prix de la ville d’Angoulême, Eisner Award (named in his honor) |

Early Life and Family Background

Will Eisner was born in Brooklyn, New York, to Jewish immigrant parents who had each faced immense personal and financial challenges upon arriving in the United States. His father, Shmuel “Samuel” Eisner, was a mural painter originally from Kolomyia, in the region of Galicia in Austria-Hungary (present-day Ukraine).

Samuel fled to the U.S. to escape military conscription and tried to support his family through a series of artistic and odd jobs, including painting backdrops for vaudeville theaters and Jewish stage productions. His mother, Fannie Ingber, was born at sea during her family’s immigration journey and endured a difficult childhood marked by the early loss of both parents. Raised by an older stepsister under strained conditions, Fannie remained largely illiterate but worked tirelessly to support her children.

The family endured financial hardship throughout Will’s youth, especially during the Great Depression. The economic strain and instability forced frequent relocations within New York, further disrupting Will’s childhood. By the age of thirteen, Eisner was already contributing to the family’s income by selling newspapers on busy street corners. These early life experiences, which exposed him to both hardship and resilience, later served as powerful inspiration for the gritty realism and emotional depth in his graphic novels.

Despite the difficult circumstances, Will’s artistic inclinations were encouraged by his father, who saw drawing as a worthwhile pursuit. Will began drawing at a very young age and immersed himself in popular culture, including pulp magazines, early cinema, and comic strips. At DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, Eisner found his creative footing. He contributed regularly to the school newspaper, The Clinton News, the literary magazine, The Magpie, and the yearbook, The Clintonian. He also participated in stage design, which further nurtured his storytelling instincts.

After high school, Eisner studied at the Art Students League of New York under the mentorship of Canadian artist George Brandt Bridgman, a master of human anatomy and dynamic figure drawing. There, Eisner sharpened his technical abilities and gained exposure to other aspiring illustrators and professionals. His education and early networking efforts opened doors to freelance opportunities in advertising illustration and in the booming pulp magazine market, where he began to carve out his career as a professional cartoonist.

Entry into Comics: The Eisner & Iger Studio

Eisner’s professional comics career began in 1936 with contributions to Wow, What A Magazine!, where he published several adventure strips that showcased his early talent for storytelling and dynamic illustration. After the magazine folded, he joined forces with fellow cartoonist Jerry Iger to form the Eisner & Iger Studio. This groundbreaking venture was one of the first comic book “packagers” that produced original content for the growing number of comic book publishers who lacked in-house creative teams. Their studio provided material to several major publishers, including Fox Comics, Quality Comics, Fiction House, and others, and was a crucial force in shaping the Golden Age of comics.

Eisner created numerous characters during this time, such as Wonder Man, an early Superman-type hero, and Blackhawk, a fighter pilot hero who became one of the era’s most popular non-superhero characters. He also had a hand in developing Doll Man, the first shrinking superhero, and a host of lesser-known but influential figures. By operating an efficient and creatively fertile studio, Eisner was not only a prolific creator but also an astute businessman, becoming financially successful and respected in the industry by the time he was in his early twenties. This period laid the foundation for Eisner’s lifelong influence on the comic book medium.

The Spirit: Redefining Comic Book Storytelling

In 1940, Eisner launched The Spirit, a weekly comic book insert distributed in Sunday newspapers, designed to appeal to an adult readership. The series followed masked detective Denny Colt, a crimefighter who returns from presumed death to battle corruption in Central City. Notable for its noir sensibilities, emotionally resonant characters, and sharp social commentary, The Spirit stood apart from other superhero fare of the time. Eisner utilized dramatic angles, splash pages, and intricate panel compositions, elevating the visual language of comics to a cinematic level. The strip also introduced a variety of supporting characters and one-off stories that showcased Eisner’s narrative range—from hardboiled mysteries to whimsical tales and social satire.

Eisner’s negotiation for ownership rights to The Spirit was groundbreaking, as most creators at the time surrendered such rights to publishers. This rare arrangement gave Eisner creative control and ensured the longevity of his intellectual property. The strip ran until 1952 and gained a reputation as a sophisticated, experimental series that deeply influenced future generations of comic creators.

During World War II, Eisner was drafted into the U.S. Army, where his artistic talents were redirected toward instructional materials. He created the character Joe Dope, a bumbling but relatable soldier used to demonstrate the importance of equipment maintenance. Eisner helped produce educational comics for Army Motors and later PS, The Preventive Maintenance Monthly, publications designed to reduce mechanical failures among military personnel. These comics combined humor with practical advice, proving that sequential art could be a powerful and effective tool for technical instruction. His military work cemented the role of comics in education and public service, a concept Eisner would champion for the rest of his career.

Graphic Novels and Literary Legacy

Eisner’s re-entry into the comics world in the 1970s marked a pivotal moment in the medium’s evolution and helped redefine what comics could achieve artistically and narratively. He was deeply inspired by the underground comix movement, which challenged traditional publishing norms and tackled controversial social issues.

This environment emboldened Eisner to pursue projects that reflected his own interest in adult themes, memory, and the human condition. In 1978, he released A Contract with God, a collection of thematically linked stories set in a fictional tenement in the Bronx, which addressed issues such as religious disillusionment, poverty, and social alienation. The book broke from the superhero genre and instead explored the raw, everyday struggles of ordinary people, effectively bridging comics and literature.

The success of A Contract with God paved the way for Eisner’s continued exploration of serious subject matter through the graphic novel format. He followed up with titles such as A Life Force, which examined the economic despair and resilience of working-class immigrants, and Dropsie Avenue, a sweeping narrative that chronicled the changing ethnic composition and cultural fabric of a single New York neighborhood over generations. His autobiographical work To the Heart of the Storm offered a deeply personal reflection on his upbringing, experiences with anti-Semitism, and the broader historical forces that shaped his worldview.

Eisner’s graphic novels blended autobiography, social critique, and experimental design, often incorporating unconventional panel layouts, expressive typography, and shifting perspectives. His work played a major role in elevating comics into a respected literary form and expanding the possibilities of sequential storytelling. In addition to his original stories, Eisner adapted classic literature and folklore into graphic narratives, including Moby-Dick, which he reinterpreted with rich visual symbolism; Sundiata, a retelling of the epic of the West African king; and Fagin the Jew, in which he sought to humanize the maligned Dickens character by providing a backstory rooted in historical prejudice. These works underscored Eisner’s belief in the power of comics to confront cultural narratives and humanize marginalized perspectives.

Educator and Theorist

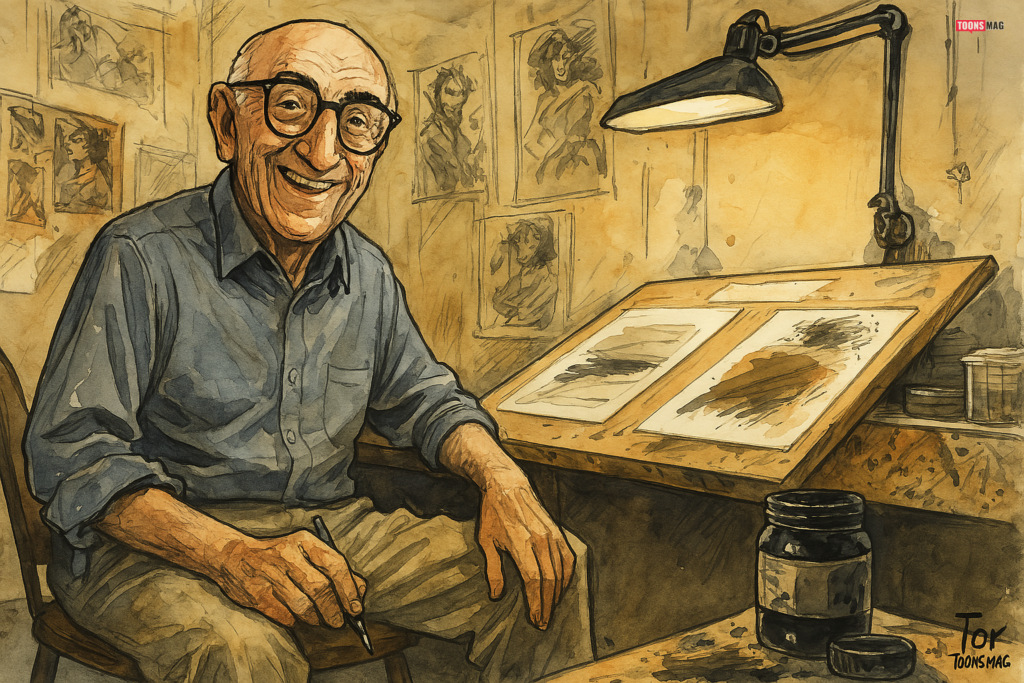

A passionate educator, Eisner taught for many years at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, where he deeply influenced a new generation of comic artists and illustrators. His teaching approach emphasized storytelling clarity, expressive character design, and the integration of visual and narrative elements to enhance emotional resonance. To support his curriculum, Eisner authored two groundbreaking textbooks: Comics and Sequential Art (1985), which explored the mechanics of storytelling through sequential images, and Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative (1996), which delved into the techniques of visual pacing, composition, and character engagement.

These texts quickly became foundational works in the field of comics education and are still widely adopted in art schools and university courses across the globe. His educational philosophy advocated for the recognition of comics as a legitimate literary and artistic medium, and he encouraged students to use personal experience and cultural heritage as sources of inspiration. His final instructional work, Expressive Anatomy, which emphasizes gesture, movement, and body language in comics, was completed posthumously and published in 2008, further cementing his legacy as both a master practitioner and a visionary educator.

Honors and Death

Will Eisner received numerous accolades throughout his career, reflecting his profound impact on the comic arts. Among his most notable honors were the National Cartoonists Society’s Reuben Award and multiple Comic Book Awards, including five from the NCS and the prestigious Inkpot Award. In 1975, he received the Grand Prix de la ville d’Angoulême in France, one of the highest international honors for a comics creator. Eisner was inducted into the Academy of Comic Book Arts Hall of Fame in 1971 and was also one of the inaugural inductees into the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame in 1987.

In 1988, the establishment of the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards (known as the “Eisners”) further cemented his legacy. These annual awards are often referred to as the “Oscars of the comic book industry,” recognizing outstanding achievements in writing, illustration, publication, and editorial excellence. Additionally, the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame was created to honor pioneers and legends of the medium, with Eisner himself among the first to be enshrined.

Eisner passed away on January 3, 2005, at the age of 87, due to complications following quadruple bypass heart surgery. His passing marked the end of a remarkable era, but his influence continues to resonate deeply within the comics and graphic novel community. His pioneering work, advocacy for comics as a literary art form, and commitment to visual storytelling education ensure that his legacy endures in classrooms, libraries, and studios around the world.

Legacy

Will Eisner is celebrated as a founding father of modern comics and a pioneer of the graphic novel form. His influence extends far beyond his most famous works, having established comics not only as a form of entertainment but also as a medium for serious, emotionally resonant storytelling. Eisner’s contributions to storytelling, education, and the legitimization of comics as a literary art form continue to shape the industry. He redefined the boundaries of comic art by integrating cinematic techniques, poignant narratives, and social commentary in a way that had never been done before.

His teaching legacy endures through his former students, many of whom have become influential artists and educators in their own right. Eisner’s textbooks remain foundational texts in comic studies programs worldwide. Academic institutions have incorporated his theories into broader visual literacy curricula, while libraries continue to expand their graphic novel collections thanks in part to the legitimacy Eisner helped establish for the medium.

From his early pulp adventures in the Golden Age of comics to his trailblazing graphic novels that explored the human condition, Eisner’s work remains a touchstone for artists, writers, educators, and scholars worldwide. In 2017, the centennial of his birth was honored with major retrospectives in New York and France, accompanied by international conferences and publications that further examined his legacy. Today, his work continues to be studied, published, and admired globally, reinforcing his place as one of the most influential figures in the history of visual storytelling.

Writings

- A Pictorial Arsenal of America’s Combat Weapons, Sterling (New York, NY), 1960.

- America’s Space Vehicles: A Pictorial Review, edited by Charles Kramer, Sterling (New York, NY), 1962.

- A Contract with God, and Other Tenement Stories, Baronet (New York, NY), 1978.

- (With P. R. Garriock and others) Masters of Comic Book Art, Images Graphiques (New York, NY), 1978.

- Odd Facts, Ace Books (New York, NY), 1978.

- Dating and Hanging Out (for young adults), Baronet (New York, NY), 1979.

- Funny Jokes and Foxy Riddles, Baronet (New York, NY), 1979.

- Ghostly Jokes and Ghastly Riddles, Baronet (New York, NY), 1979.

- One Hundred and One-Half Wild and Crazy Jokes, Baronet (New York, NY), 1979.

- Spaced-Out Jokes, Baronet (New York, NY), 1979.

- The City (narrative portfolio), Hollygraphic, 1981.

- Life on Another Planet (graphic novel), Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1981.

- Will Eisner Color Treasury, text by Catherine Yronwode, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1981.

- Illustrated Roberts Rules of Order, Bantam (New York, NY), 1983.

- Spirit: Color Album, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1981–1983.

- (Catherine Yronwode, with Denis Kitchen) The Art of Will Eisner, introduction by Jules Feiffer, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1982.

- (Coauthor, with Jules Feiffer and Wallace Wood) Outer Space Spirit, 1952, edited by Denis Kitchen, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1983.

- The signal from Space, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1983.

- Will Eisner’s Quarterly, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1983–86.

- Will Eisner’s 3-D Classics Featuring. ., Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1985.

- Comics and Sequential Art, Poorhouse (Tamarac, FL), 1985.

- Will Eisner’s Hawks of the Seas, 1936-1938, edited by Dave Schreiner, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1986.

- Will Eisner’s New York, the Big City, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1986.

- Will Eisner’s The Dreamer, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1986.

- The Building, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1987.

- A Life Force, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1988.

- City People Notebook, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1989.

- Will Eisner’s Spirit Casebook, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1990–98.

- Will Eisner Reader: Seven Graphic Stories by a Comics Master, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1991.

- To the Heart of the Storm, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1991.

- The White Whale: An Introduction to “Moby Dick,” Story Shop (Tamarac, FL), 1991.

- The Spirit: The Origin Years, Kitchen Sink (Princeton, WI), 1992.

- Invisible People, Kitchen Sink (Northampton, MA), 1993.

- The Christmas Spirit, Kitchen Sink (Northampton, MA), 1994.

- Sketchbook, Kitchen Sink (Northampton, MA), 1995.

- Dropsie Avenue: The Neighborhood, Kitchen Sink (Northampton, MA), 1995.

- Graphic Storytelling, Poorhouse (Tamarac, FL), 1996.

- (Adapter) Moby Dick by Herman Melville, NBM (New York, NY), 1998.

- A Family Matter, Kitchen Sink (Northampton, MA), 1998.

- (Reteller) The Princess and the Frog by the Grimm Brothers, NBM (New York, NY), 1999.

- Minor Miracles: Long Ago and Once Upon a Time, Back when Uncles Were Heroic, Cousins Were Clever, and Miracles Happened on Every Block, DC Comics (New York, NY), 2000.

- The Last Knight: An Introduction to “Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes, NBM (New York, NY), 2000.

- Last Day in Vietnam: A Memory, Dark Horse (Milwaukie, OR), 2000.

- Will Eisner’s The Spirit Archives, DC Comics (New York, NY), 2000.

- The Name of the Game, DC Comics (New York, NY), 2001.

- Will Eisner’s Shop Talk, Dark Horse (Milwaukie, OR), 2001.

- (With Dick French, Bill Woolfolk, and others) The Blackhawk Archives, DC Comics (New York, NY), 2001.

- Fagin the Jew, Doubleday (New York, NY), 2003.

- (Adapter) Sundiata: A Legend of Africa, NMB (New York, NY), 2003.

- For U.S. Department of Defense, creator of comic strip instructional aid, P. S. Magazine,1950, and for U.S. Department of Labor, creator of career guidance series of comic booklets, Job Scene, 1967. Also creator of comic strips, sometimes under pseudonyms Will Erwin and Willis Rensie, including “Uncle Sam,” “Muss ’em Up Donovan,” “Sheena,” “The Three Brothers,” “Blackhawk,” “K-51,” and “Hawk of the Seas.” Author of newspaper feature, “Odd Facts.” Also a contributor to Artwork for “9-11 Emergency Relief,” issued by Alternative Comics, 2001.

Sidelight

Cartoonist Will Eisner, the creator of many popular comic strips, was also well known as a pioneer in the educational applications of this medium. Throughout his fifty-plus-year career, he created a host of comic-book characters to guide young people in their choice of a career, to instruct military personnel, and simply to entertain children of all ages.

Will Eisner has also produced a series of comic-book training manuals for developing nations, which teach modern farming techniques and the maintenance of military equipment. These booklets are used by the Agency for International Development, the United Nations, and the U.S. Department of Defense.

Will Eisner’s career began in the mid-1930s when he sold his first comic feature, “Scott Dalton,” to Wow! magazine. He went on to create more comic strips, including “Sheena, Queen of the Jungle” and his best-known work, “The Spirit,” a weekly adventure series published as an insert in Sunday papers from 1940 to 1951.

This strip featured protagonist Denny Colt, a private investigator who is seriously injured, and presumed dead, after an explosion in the laboratory of evil scientist Dr. Cobra. Once Colt recovers, he vows to exploit his new anonymity to enhance his ability to bring hardened criminals to justice. The strip, renowned for its social satire, also featured the first African-American character to make ongoing appearances in an American comic feature.

In 1942, Eisner was drafted into the U.S. Army, where he was put to work designing safety posters. He also used cartoon-strip techniques to simplify the military’s training manual for equipment maintenance, ArmyMotors. After his discharge in 1946, Will Eisner continued to write and illustrate “The Spirit,” but decided to discontinue the strip in 1951.

He then founded the American Visuals Corporation, a company that produced comic books for schools and businesses. In 1967, the U.S. Department of Labor asked Eisner to create a comic book that would appeal to potential school dropouts. The result was Job Scene, a series of booklets designed to introduce career choices to young people in the hope that they would see the need for further education. Job Scene proved so successful that several national publishers have issued similar series.

Eisner also developed P.S. Magazine, an instructional manual for the U.S. Department of Defense designed to replace the verbose, unwieldy technical manuals formerly used by military trainers. Eisner wrote in a 1974 article for Library Journal: “The significance of comics as a training device is perhaps not so much the use of time-honored sequential art as the language accompanying the pictures.

For example, P.S. Magazine . . . employed the soldier’s argot, rendering militarise into common language. The magazine said ‘Clean away the crud from the flywheel’ instead of ‘All foreign matter should be removed from the surface of the flywheel and the rubber belt which it supports.'” Eisner’s version reduced the original one-hundred-word section describing that procedure to a sequence of three panels which quickly and simply presented the necessary instruction.

The immediate visual impact and simple language used in P.S. Magazine are assets which Eisner believes make comics desirable in more traditional classroom situations.

Critics, however, complain that while teachers are trying to instill a healthy respect for proper language, comic books and strips violate every rule of grammar. In his Publishers Weekly article, Eisner responded: “This is an understandable criticism, but it is based on the assumption that cartoons are designed primarily to teach language. Comics are a message in themselves... To readers living in the ghetto and playing in the street and schoolyard, comic books, with their inventive language, argot, and slang, serve as no other literature does.”

Eisner believes it is remarkable that many reading teachers are still reluctant to adopt this “inviting material.” He praises those educators who have recognized the merit in his art form.

Eisner concluded his Publishers Weekly article with a commentary on the improving status of comics in the schools: “In schools, comic strip reprints are reaching reluctant readers who are either unresponsive or hostile to traditional books… Certain qualities distinctive to comic books support their educational importance. Perhaps their most singular characteristic is timeliness. Comics appeal to readers when they deal with ‘now’ situations, or treat them in a ‘now’ manner. Working in a high-speed transmission, the author faces instant acceptance or rejection.

He or she is writing for a transient audience who are in a hurry to savor vicarious experiences. Loyalties are to the characters themselves, so the need for imaginative storytelling is great. Equally vital is the choice of terms. The reader’s instant recognition of symbols and concepts challenges the ingenuity and empathy of comic-book creators.”

Satisfying as his educational-and vocational-based work had been, Eisner was drawn back to narrative forms again in the mid-1970s, after he attended a comic-book convention and was inspired by the innovative work he saw there, in particular, that of underground cartoonist R. Crumb. In 1975 he began work on what he called a “graphic novel,” published three years later as A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories. Unlike his earlier adventure comics, this work is a serious treatment of such serious themes as religious faith, sexual betrayal, and prejudice.

Other graphic novels, which depicted the lives of Jewish immigrants in America, followed, including Life on Another Planet, Big City, A Life Force, and Minor Miracles. Eisner’s 2001 graphic novel, The Name of the Game, is a multigenerational family saga about the Arnheim family, who expand their businesses from corset manufacturing to stockbrokers. Though Booklist reviewer Gordon Flagg found the book melodramatic and predictable, the critic appreciated Eisner’s “expressive” artwork and noted that the book reflects “a sensibility somehow appropriate to the period and subject.”

Eisner has also used the comic-strip medium to adapt literary classics, including Don Quixote and Moby Dick as well as fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. These projects have received mixed reviews. Susan Weitz of School Library Journal found Eisner’s version of Moby Dick“simplistic” and disappointing; Booklistcontributor Francisca Goldsmith, however, considered it highly successful in conveying the original work’s plot, characterizations, and mood. Similar differences marked critical reception to the last Knight: An Introduction to “Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes.

Marian Drabkin commented in School Library Journal that, in Eisner’s hands, Don Quixote becomes merely a “clownish madman whose escapades are slapstick and pointless,” while Cervantes depicted him as a much more complex character. Booklist critic Roger Leslie, on the other hand, felt that Will Eisner’s book is “faithful to the spirit of the original” and an excellent introduction to the great classic.

In Comics and Sequential Art, Will Eisner explains the unique aspects of sequential art: imagery, frames, timing, and the relationship between the written word and visual design. Ken Marantz, reviewing the book’s twenty-first printing for School Arts, praised its clarity, creativity, and detailed descriptions, and concluded that the book is a valuable introduction to an innovative medium for creative expression.

Despite being an octogenarian, Will Eisner has continued to work vigorously. In Fagin the Jew, published in 2003, Eisner takes the famous character from Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist and tells his personal story, one in which Fagin comes out in a much better light. As told by Eisner, Fagin was virtually forced into crime as a youth because of circumstances, not the least of which was the general prejudice against his family as Ashkenazi Jews.

“As written by Will Eisner, Fagin gains depth and humanity, and he could have found success on the right side of the law had not persecution, poverty, and bad luck hindered him,” wrote Steve Raiteri in Library Journal. The graphic novel includes a foreword explaining the probable historical antecedents of the tale and how they related to Dickens’s portrayal of Jews.

While noting that Will Eisner’s depiction of nineteenth-century London is “wholly convincing,” a Publishers Weekly reviewer felt that “the story errs on the side of extreme coincidence and melodrama.” Library Journal contributor Steve Weiner commented that “Will Eisner masterfully weaves a Dickensian story of his focusing on racism and stereotypes.” Francisca Goldsmith, writing in School Library Journal noted that the book would appeal to readers looking for another view of the Dickens classic but was “also for those concerned with media influence on stereotypes and the history of immigration issues.”

In another 2003 publication, Will Eisner adapted an African story set in the thirteenth century for the graphic novel, Sundiata: A Legend of Africa. The story revolves around the death of the Mali peoples’ leader and their subsequent conquest by a tyrant, who can control the elements. Sundiata, son of the former Mali leader, eventually leads his people in the victory against their oppressor.

Booklist contributor Carlos Orellana felt that the ending was unsatisfying but noted that “the plot flows smoothly; the telling never feels rushed; and the sequential art, which is full of movement and expression, gives the familiar good-versus-evil theme extra depth.” Steve Raiteri, writing in Library Journal, commented that the book would interest not only children but that teens and adults as well would “appreciate Eisner’s concise and clear storytelling and his dramatic artwork, distinctively colored in grays and earth tones.”

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!

2 Comments