Sergio Aragonés Domenech, born on September 6, 1937, in Sant Mateu, Castellón, Spain, is synonymous with speed in cartoons. Widely recognized as “the world’s fastest cartoonist,” Aragonés is celebrated for prolific contributions to Mad magazine and for creating the comic book Groo the Wanderer.

Sergio Aragonés

- Born: September 6, 1937

- Birthplace: Sant Mateu, Spain

- Occupation: Cartoonist, Writer, Artist

Notable Works:

- Groo the Wanderer (Comic Series)

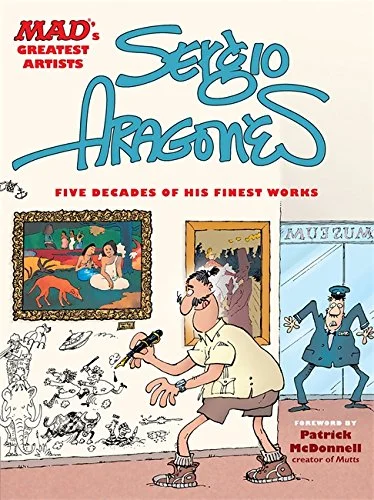

- MAD Magazine (Contributor)

- Sergio Aragonés Funnies (Comic Series)

- The Groo Chronicles (Book Series)

Awards:

- National Cartoonists Society Award (Various)

- Eisner Award (Multiple)

Notable Style:

- Humorous and Satirical Cartoons

- Detailed and Expressive Artwork

“I don’t know precisely what caused Sergio Aragonés to create Groo and I don’t know that he could tell you, either. But…I’m sure it had a lot to do with wanting to have a character he could call his own. Which, at the time, was not so easy to have.”

Early Life and Artistic Passion

Aragonés’s artistic journey began against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War. His family, seeking refuge, emigrated to France before settling in Mexico when Aragonés was just six. His early passion for art was evident; a story recounts a young Aragonés alone in a room with a box of crayons, covering the walls with hundreds of drawings.

Despite initial challenges in a new country, Aragonés used his drawing skills to connect with others. Drawing became not just a form of expression but a means of assimilation. His first taste of earning money came from classmates paying him to draw illustrations for their homework.

MARK EVANIER, ARAGONÉS’S LONGTIME FRIEND

Sergio Aragonés has achieved enormous success as a cartoonist. Legendary Peanuts creator Charles Schulz (1922–2000) told the Los Angeles Daily News that “Sergio’s one of the most admired cartoonists in the business.”

Aragonés first made a name for himself as a contributor to Mad magazine, starting in 1963, and went on to earn the comic industry’s highest accolades, winning the Reuben Award for Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year from the National Cartoonists Society in 1996; a Will Eisner Award in 1992, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2000, and 2001; a Harvey Award for Humor in 2000 and 2001; and the Will Eisner Hall of Fame Award in 2002.

Sergio Aragonés has achieved special attention as a graphic novelist for his satiric tales about Groo, a bumbling barbarian who makes more trouble than he solves. Published since 1981, Groo has become a “classic comic character,” according to Publishers Weekly, and the Groo stories, which began as parodies of stories about Conan the Barbarian, have become some of the longest-running humorous comic books in history.

Started cartooning in third grade

Sergio Aragonés was born in Castellon, Spain, on September 6, 1937. A bloody civil war in Spain at the time prompted Pascual and Isabel Aragonés to move with their six-month-old son to a refugee camp in France. As World War II(1939–45; the war in which Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, the United States, and their allies defeated Germany, Italy, and Japan) started to tear apart Europe, the Aragonés family moved again, settling in Mexico.

Art and Academia

Aragonés’ artistic journey continued as he sold his gag cartoons to magazines while studying architecture at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). His unique approach to combining art and humor caught the attention of many.

Notably, he delved into the pantomime world under Alejandro Jodorowsky’s guidance. This experience shaped Aragonés’ understanding of physical movement, influencing his later comic creations.

In 1962, armed with $20 and a portfolio of drawings, Aragonés arrived in New York. Despite limited knowledge of English, he sought entry into the world of Mad magazine, guided by the suggestion of fellow artist Antonio Prohías, creator of “Spy vs. Spy.”

Best-Known Works

Graphic Novels

- Groo the Wanderer (1982).

- The Groo Adventurer (1990).

- The Death of Groo (1991).

- Groo the Wanderer (1991).

- The Groo Dynasty (1992).

- The Groo Exposé (1993).

- The Groo Bazaar (1993).

- The Life of Groo (1993).

- The Groo Festival (1993).

- Groo: The Most Intelligent Man in the World(1998).

- The Groo Inferno (1999).

- The Groo Handbook (1999).

- The Groo Lunch Box (1999).

- The Groo Jamboree (2000).

- Groo and Rufferto (2000).

- Groo: Mightier than the Sword (2001).

- The Groo Kingdom (2001).

- The Groo Library (2001).

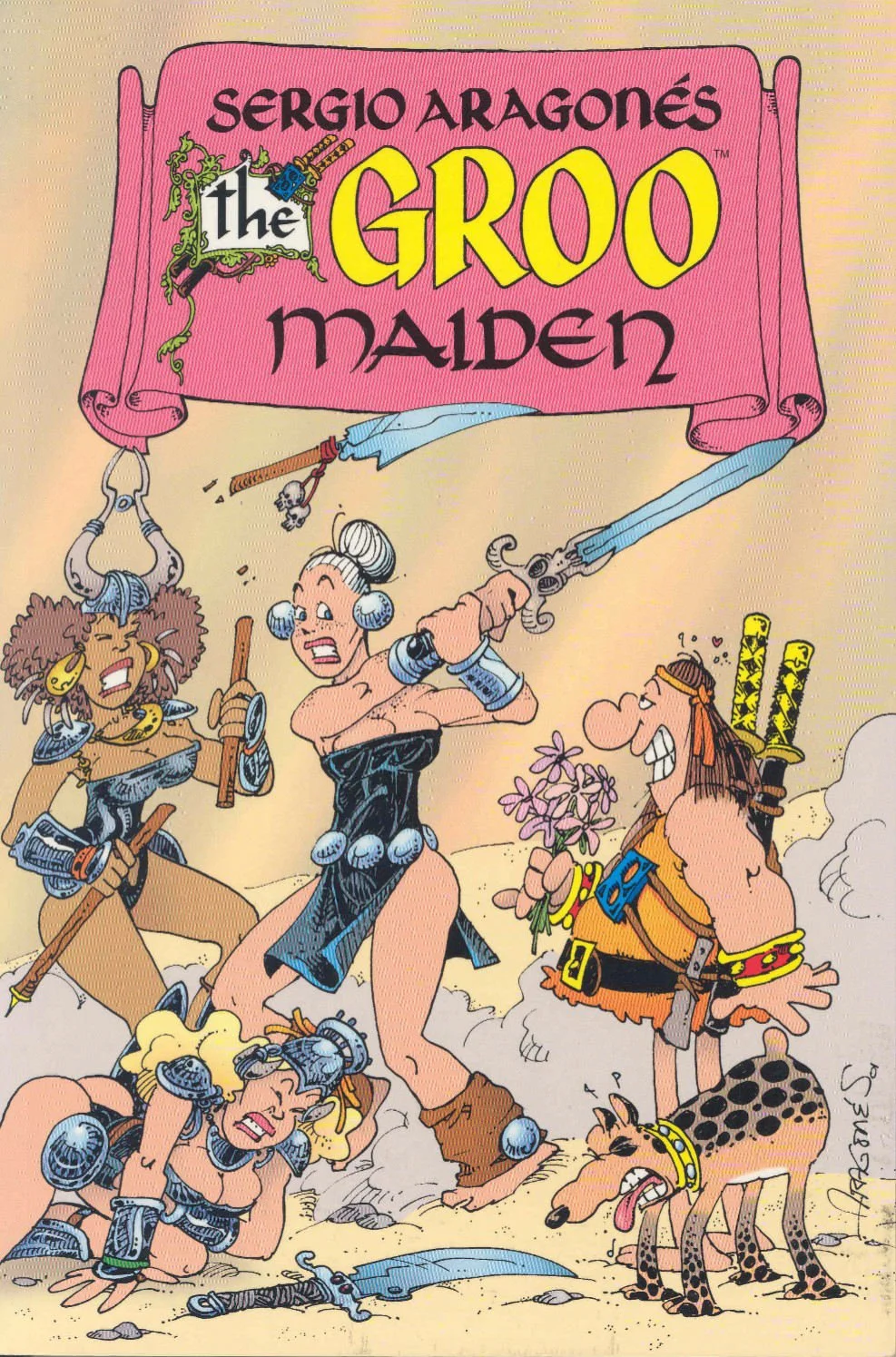

- The Groo Maiden (2002).

- The Groo Nursery (2002).

- Groo: Death and Taxes (2002).

- The Groo Odyssey (2003).

Other

Boogeyman (1999).

Fanboy (2001).

As a child, drawing became one of Sergio Aragonés’s favorite pastimes. He found inspiration from Mexican comic magazines and U.S. comic strips. By the third grade, he entertained his classmates with his cartoons, which included funny doodles of his teachers. He drew wordless cartoons in which his characters’ actions told the story.

Sergio Aragonés continued his cartooning into high school and developed a fan base with his classmates, one of whom was convinced that Aragonés was good enough to turn professional and sent some of his work to a Mexican magazine. The magazine offered to buy some of his work, and at age seventeen Aragonés sold his first cartoons for just enough money to take his friend to dinner as thanks for submitting his work. From that time on, Aragonés sold his work to various Mexican publications.

After high school, Aragonés briefly studied engineering, then architecture at the University of Mexico, but he remained true to his first passion: cartooning. Aragonés drew six cartoons each week for publication in Mañanamagazine, a routine he maintained for ten years.

In addition to his architecture studies and cartooning, Aragonés learned pantomime (a performance art that uses body movements as the only means of communication) and performed on weekends with a professional troupe. By 1962, Aragonés had determined that he wanted to become a full-time cartoonist, and after attending college for three years he dropped out. “I knew I was going to make it as a cartoonist,” he told the Los Angeles Daily News. “There couldn’t have been another life for me.”

Immigrated to the United States

Aragonés moved to New York City to get himself started. As he shopped his cartoons around town, he made ends meet by playing the guitar for tips on the streets and at a Greenwich Village coffee-house. It wasn’t long until he found a buyer for his cartoon work, however. Mad magazine contributor Antonio Prohias (1921–1998), the creator of the wordless Spy vs. Spy series, admired Aragonés’s work and showed it to his coworkers, including Mad editor Al Feldstein, who offered Aragonés $200 for ten of his cartoons. “Wow, I couldn’t believe it!” Aragonés recalled in Cartoonist Profiles.

Aragonés had long been a fan of Mad magazine, and he related to the Los Angeles Daily News that “I never fathomed I would work for them. They were too good and in another country, in a language, I didn’t know.”

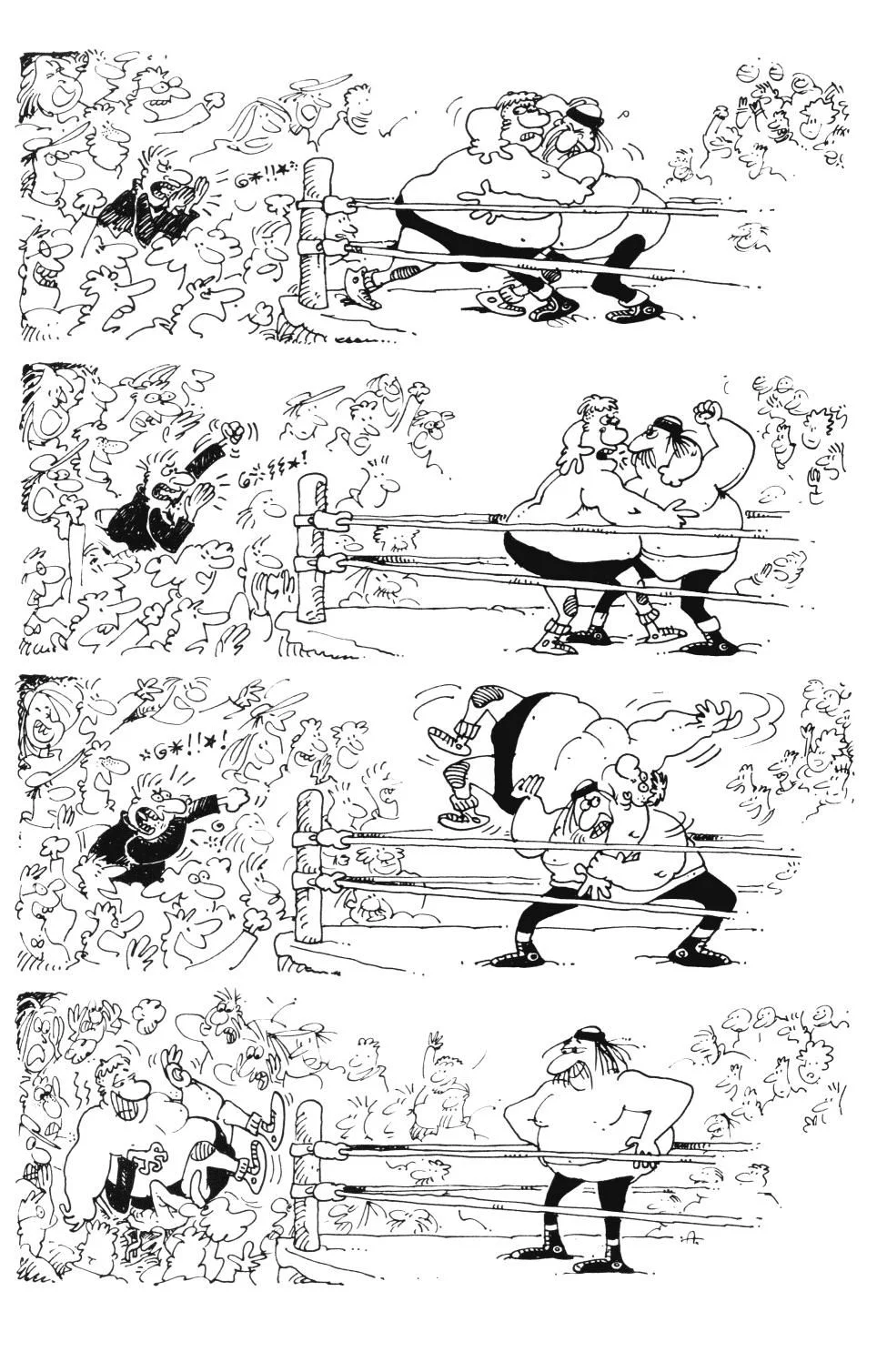

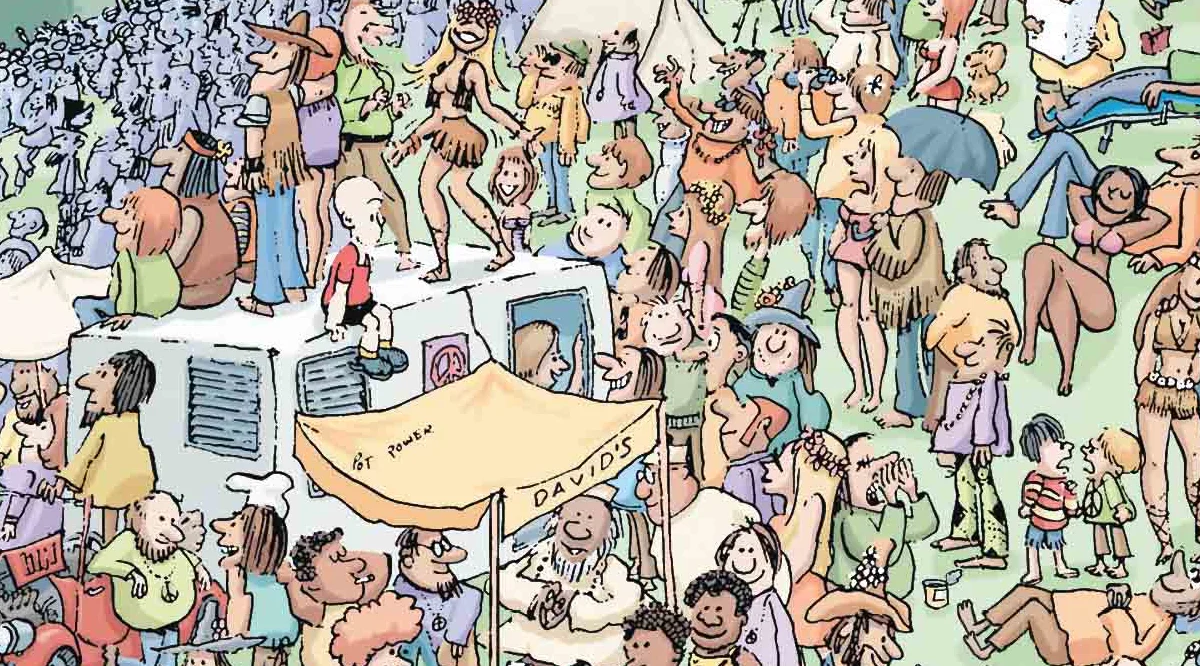

But Aragonés’s drawings communicated without words. Through his characters’ actions, facial expressions, and the environments in which he placed them, Aragonés poked fun at everything from politics, religion, school, and family gatherings, to film and television, and society in general.

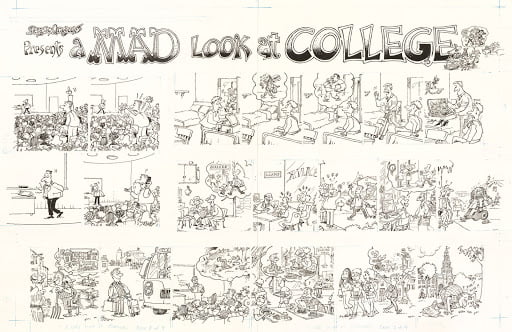

Since the January publication of Mad #76 in 1963, Aragonés has published cartoons in the margins, between other comic strip panels, and in the corners of pages in each volume of Mad magazine except one. The only reason for his omission from that one volume was a delay in the mail service; he had tried to send his work to Mad while on a trip to Europe. His work in the margins of Mad brought him celebrity status in the comics industry.

Renowned work ethic

Aragonés developed a reputation for his near-constant—and very speedy—drawing. “The only time I don’t use my pen is when I’m sleeping,” Aragonés noted in Columbus Alive. Along with his furious output, Aragonés prides himself on constantly coming up with new ideas. He noted on the Sergio Aragonés Web site (which is maintained by Mark Evanier) that for each issue of Mad, “I send four pages of finished marginals and they select the ones they need.

I have 40 years of unpublished material, the ones they don’t pick, and the reason I don’t redraw them or use them again is that I like to use my brain every day and come up with new jokes.…

Sometimes, it fails but generally, I know that what I produce is new. Of course, they are often variations on the same subject, as you can see. Maybe when I’m old (older) and my brain doesn’t work correctly, I’ll start using the unpublished gags in my files. Meanwhile, count on me sitting in the coffee house, thinking up new material.”

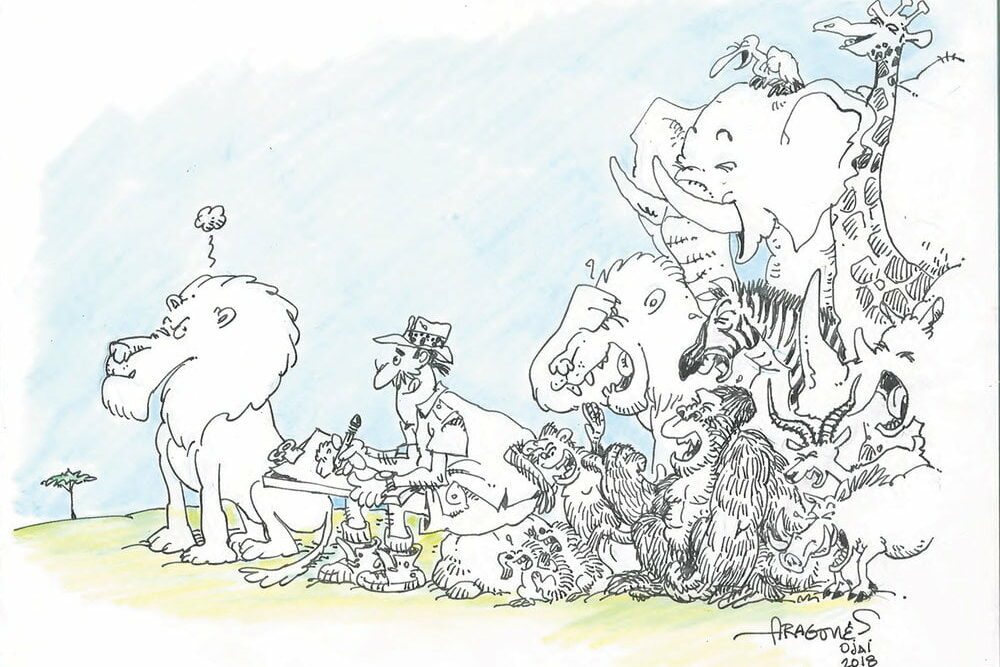

For his inspiration, Aragonés turns a critical eye to people’s everyday experiences. He explained to the Los Angeles Daily News that cartoonists are “critical of everything. They see the foibles of man. The weaknesses of man. The abuses that man inflicts onto men.” Keen observation is the key to Aragonés’s research, which “takes a great percentage of my time,” Aragonés related on his Web site.

For his, Mad Look At … series for which he drew several panels about a specific topic—sharks, for instance—from a variety of perspectives, Aragonés spent weeks researching, reading, talking to people, watching television and movies, and visiting places such as flea markets. Knick-knacks he’s picked up in various places littered his workplace. He also relied on photographs from his travels—he’s visited more than one hundred countries over the years—and his collection of National Geographic magazines.

Aragonés’s work is noted for its freshness and spontaneity. Aragonés never sketched his ideas in pencil first. For the most part, he relied on his Pelikan fountain pen filled with Badger brand non-acrylic black ink to capture the essence of his ideas immediately on paper.

“I believe in the sketch as the final form of art,” Aragonés related to Cartoonist Profiles, noting that if he tried to ink over pencil sketches, his lines would lose their vigor. But Aragonés noted on his Web site that “Once in a while, I use a brush to fill up large black areas.” And for his drawings that would be reduced to a very small size in the margins of Mad, he preferred to draw with a Rapid-o-Graph technical pen.

Mark Evanier, Aragonés’s Collaborator

Sergio Aragonés’s longtime friend, Mark Evanier (1952–), wrote the witty dialogue that complemented Aragonés’s illustrated stories of Groo, as well as several other comic books. Just as Aragonés knew from a young age that he would be a cartoonist, Evanier knew that he would be a writer. Less than a week after graduating from high school in 1969, Evanier sold his first magazine stories, and within a year he landed a job with comic legend Jack Kirby, becoming what he termed Kirby’s “utterly-unnecessary assistant,” according to his POVonline Web site.

After apprenticing with Kirby for a few years, Evanier went on to write comics for Disney and Warner Brothers, including stories about the well-known characters Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Woody Woodpecker, and Scooby-Doo. By the 1970s, he had begun writing scripts for film and television, but quickly sought out more comic book writing with Hanna-Barbera and DC Comics.

Evanier described to Dark Horse editor Shawna Ervin-Gore how his collaboration with Aragonés started. He met Aragonés in 1968 when Aragonés spoke at the comic book club that Evanier presided over as president. “[H]e was one of the first professional cartoonists—alleged professional cartoonists—I’d ever met. We quickly became friends and for several years kept saying ‘you know, we oughtta work together someday.”‘

When Aragonés first completed a story about his goofy barbarian, Groo, he approached Evanier, and said, “I’m not taking the rap for this on my own …,” as Evanier told Ervin-Gore.

Evanier agreed to write the dialogue for the stories, and since the first publication of Groo the Wanderer in 1982, Evanier and Sergio Aragonés have collaborated on what Evanier estimated to be eight thousand Groo stories, a comic series for Dark Horse called Boogeyman, and another for DC Comics called Fanboy. But, as Evanier confided to Ervin-Gore, his work with Aragonés was just an excuse for “Sergio to come over and we go to Sizzler [a steakhouse] and eat together and Sergio draws on napkins and we laugh and we call this a collaboration.”

While Sergio Aragonés’s reputation was built on his work for Mad, his prolific output went far beyond the magazine. By the late 1960s, he began working on comic books for DC Comics. Although publishers asked Aragonés to develop comic characters, he had refused because none would grant him the copyright to his creation. “The publishers just paid the artists a flat fee per page,” he explained to Charles Solomon of the Los Angeles Times. “They didn’t share the royalties as the paperbacks did. I wasn’t going to give away any creations like that.”

The Mad Magazine Odyssey

A language barrier marked Aragonés’s first encounter with Mad. However, his cartoons spoke a universal language of humor. Mad’s editor, Al Feldstein, was so impressed that Aragonés became a regular contributor in 1963.

Facing financial challenges, Aragonés found a unique solution — he spent so much time at Mad’s office that publisher Bill Gaines allowed him to sleep there overnight. This generosity fostered a relationship until 2020, when Mad transitioned to a predominantly reprint format.

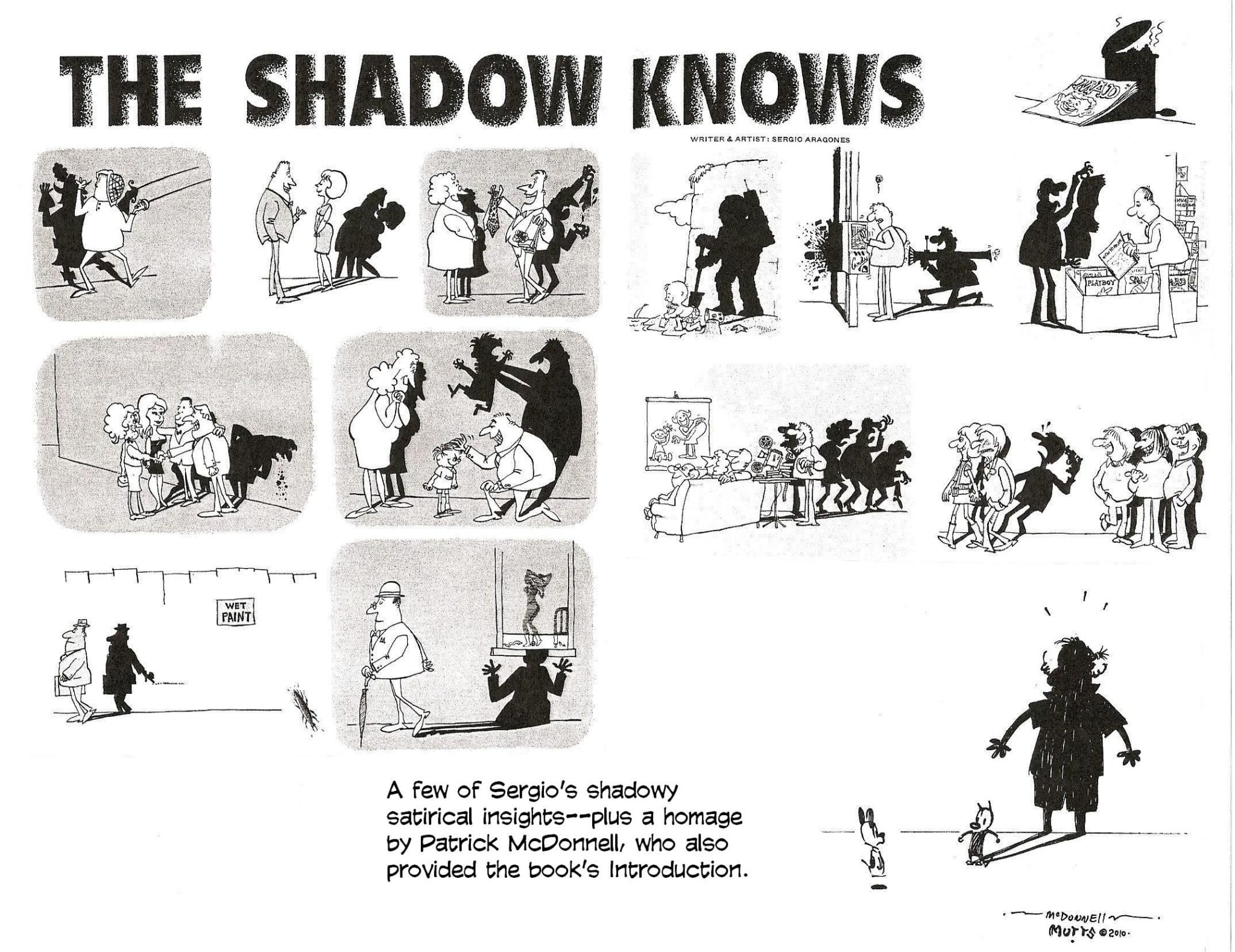

The Marginals Maestro

Aragonés’s creativity extended to the famous “marginals” in Mad magazine. These wordless, drawn-out dramas became his signature. He transformed the magazine’s margins, creating a steady stream of small cartoons that became a beloved feature.

Al Jaffee once humorously remarked that Aragonés had drawn more cartoons on napkins than most cartoonists in their careers. The “Marginal Thinking” had become Mad’s integral and cherished part.

Groo the Wanderer and Beyond

In the late 1970s, Aragonés conceived Groo the Wanderer, a humorous barbarian whose exploits wouldn’t grace the pages until 1982. Groo, named for its meaninglessness in any language, became a testament to Aragonés’ creative resilience.

Collaborating with writer Mark Evanier, Aragonés navigated the comic book industry’s challenges, including Groo’s survival through different publishers. Groo has become an enduring character in the comic world, showcasing Aragonés’ ability to create something timeless and uniquely humorous.

Groo

The difficulties of negotiating with publishers did not stop Sergio Aragonés from imagining his characters. Sergio Aragonés’s years of drawing on napkins in restaurants, on hotel stationary, and other scraps filled drawers in his studio and home. He kept them with the idea that someday they might prove useful.

In 1976 or 1977, Aragonés pulled from his files some pictures of a funny-looking barbarian character to show his friend, the comic writer Mark Evanier (1952–). In the late 1970s, Conan the Barbarian and other such warrior heroes were quite popular.

Sergio Aragonés wanted to use his character, which he named Groo, to poke fun at the barbarian hero genre. And he wanted to figure out a way to own the copyright to his creation. In the early 1980s, Sergio Aragonés negotiated such a deal with the now-defunct publisher Pacific Comics in San Diego, California. Evanier agreed to write the dialogue for Aragonés’s stories.

Groo the Wanderer was introduced in 1982, and Sergio Aragonés and Evanier have continued to publish new Groo stories ever since. Groo is a kindhearted but idiotic warrior hero whose attempts to save the day more often than not end up making things much worse in the fictional land of Plenty. Over the years, Groo has tried to save citizens from the evil ways of tyrants, to help the homeless, and has even fallen in love with a nasty warrior princess. And Groo’s destructive tendencies wreak havoc throughout every story.

While Groo’s own, mostly accidental exploits are humorous in themselves, he is joined by a huge cast of comic characters, most notably his faithful dog, Rufferto, that makes the stories even funnier. Groo’s misadventures have sunk the ships of both friend and foe, ruined ecosystems, destroyed whole towns, and even started bloody wars. While the characters’ temperaments remain constant throughout the stories, the topics explored are too numerous to count, and fans have come to expect the unexpected from Sergio Aragonés and Evanier.

Looking toward the future

Nearly five decades after publishing his first work, Sergio Aragonés has yet to slow down. In an interview with Dark Horse editor Shawna Ervin-Gore, Aragonés explained his work on Boogeyman, the humorous horror stories he started creating with Mark Evanier in 1998, and remarked that he would eventually “like to touch all the genres.… I’d love to do a whole series of stories that would be Westerns, and science fiction, and detective stories, and horror stories, and have them collected into books.”

But as he looked forward to exploring new genres, Sergio Aragonés told Ervin-Gore that he did not expect to stop working on new Groo adventures: “With Groo, all the stories come naturally. I can’t see quitting Groo. We have so many stories to tell about him.” And indeed, although Aragonés has published an amazing number and variety of comic strips, Groo remained prominent among his work into the 2000s.

Awards and Legacy

Sergio Aragonés’s work has not gone unnoticed. He received numerous awards, including Shazam Awards, Harvey Awards, and the prestigious Eisner Award in 1992, making him the first Mexican to achieve this honor.

In popular culture, Aragonés made a Futurama appearance, preserving his head in 3010. His influence extends beyond cartoons; an award in the Comic Art Professional Society is named “The Sergio” in homage to his remarkable contributions.

Sergio Aragonés Domenech’s journey from being a young artist in Spain to becoming the fastest cartoonist in the world is a testament to passion, resilience, and a unique sense of humor. His impact on Mad magazine, the creation of Groo the Wanderer, and his distinctive “marginals” have left an indelible mark on the world of cartoons, making him a true icon in comic art.

For More Information

Books

- Evanier, Mark. Mad Art: A Visual Celebration of the Art of Mad Magazine and the Idiots Who Create It. New York: Watson-Guptill, 2003.

- Meglin, Nick. The Art of Humorous Illustration.New York: Watson-Guptill, 1973.

Periodicals

- Cartoonist Profiles no. 97 and no. 98 (August 1970).

- Greenberg, David. “What, Him Worry?; Mad Cartoonist Lets His Work Do the Talking.” Daily News (Los Angeles, CA) (September 27, 1998): p. L6.

- “Malibu Comics to Debut ‘The Mighty Magnor,’ New by Mad Magazine Artist Sergio Aragones, in April on QVC Network.” PR Newswire (March 22, 1993).

- Mozzocco, J. Caleb. “Mad Man: Sergio Aragones Sketches Out Half a Life in Cartooning.” Columbus Alive (November 30, 2000): p. 13.

- Solomon, Charles. “Cartoonist Aragones Is Mad about His Work.” Los Angeles Times (August 7, 1987): p. 1.

- Woodard, Josef. “PROFILE Cartoonist Has Been on Cutting Edge for 30 Years Sergio Aragones of MAD Magazine Does His Work in the Margins. The Ojai Resident Is Being Featured in a Show at Oxnard’s Carnegie Art Museum.” Los Angeles Times (December 2, 1993): p. 9.

- Zaleski, Jeff. “Groo: Death and Taxes.” Publishers Weekly (June 2, 2003): p. 36.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions) about Sergio Aragonés Domenech

Who is Sergio Aragonés Domenech?

Sergio Aragonés Domenech is a Spanish/Mexican cartoonist and writer renowned for his work in Mad magazine and as the creator of the comic book Groo the Wanderer.

What is Sergio Aragonés best known for?

Sergio Aragonés is best known for his contributions to Mad magazine and as the creator of the comic book Groo the Wanderer.

How do his peers and fans describe Sergio Aragonés?

Aragonés is widely regarded as “the world’s fastest cartoonist” by his peers and fans.

What has The Comics Journal said about Sergio Aragonés?

The Comics Journal has described Sergio Aragonés as “one of the most prolific and brilliant cartoonists of his generation.”

What did Mad editor Al Feldstein say about Sergio Aragonés?

Mad editor Al Feldstein stated, “He could have drawn the whole magazine if we’d let him.”

Where and when was Sergio Aragonés born?

Sergio Aragonés was born in Sant Mateu, Castellón, Spain, on September 6, 1937.

How did Sergio Aragonés use drawing during his early life in Mexico?

Sergio Aragonés used his drawing skills to assimilate into his new environment in Mexico. He would draw illustrations for classmates, earning money by completing their homework drawings.

When did Sergio Aragonés arrive in the United States, and how did he start contributing to Mad magazine?

Sergio Aragonés arrived in New York in 1962 with $20 and his portfolio. Initially unsure about fitting into Mad’s style, he went to Mad’s offices but ultimately became a contributor after his astronaut cartoons were arranged into a themed article.

What is Sergio Aragonés’s contribution to Mad magazine known as?

Sergio Aragonés has a featured section in every issue of Mad called “A Mad Look At…” where he presents 4 to 5 pages of speechless gag strips known for their humor and creativity.

What are some notable awards won by Sergio Aragonés?

Sergio Aragonés has won numerous awards, including Shazam Awards, Harvey Awards, Inkpot Award, Eisner Award, and the prestigious Reuben Award for his contributions to Mad and Groo the Wanderer.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!

One Comment