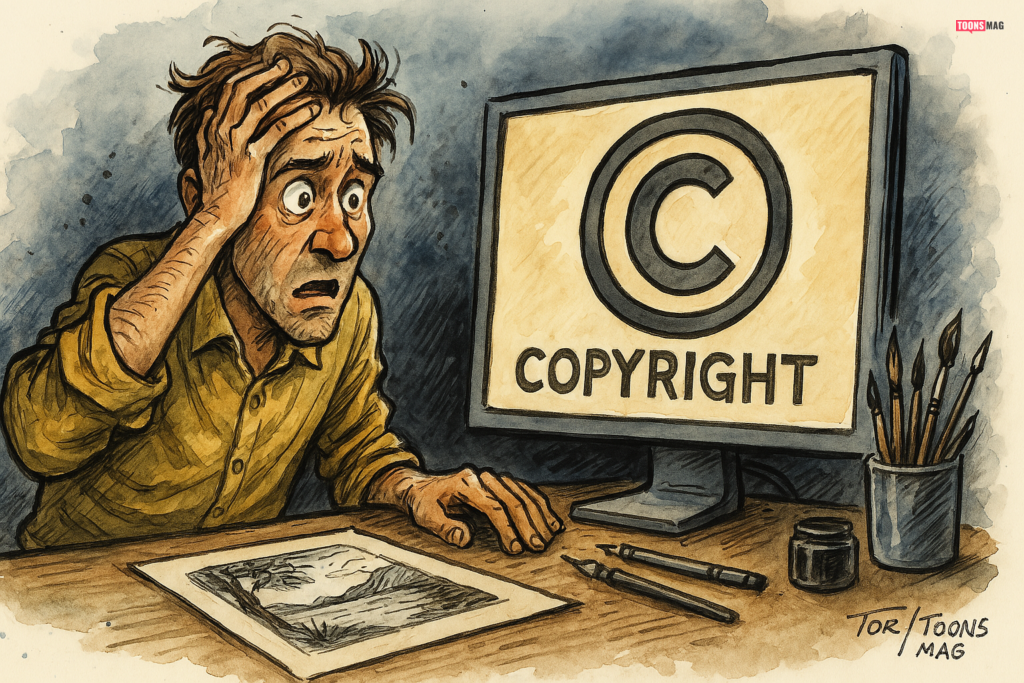

Inspiration vs. Copying: In the ever-evolving world of visual storytelling, the distinction between inspiration and copying continues to spark debate among artists, critics, and legal experts. For cartoonists and illustrators, the creative process often involves reference images—be it a photo, another artist’s work, or a real-life scene. But when does referencing become copying? More crucially, at what point does it become copyright infringement?

This article explores the nuanced relationship between inspiration, copying, and copyright. By drawing on historical cases, artistic principles, and intellectual property law, we aim to demystify the fine line that separates homage from plagiarism and creative borrowing from legal violation.

1. The Role of Inspiration in Artistic Growth

Art does not exist in a vacuum. Every artist is influenced by others, whether through admiration, study, or cultural exposure. This process of drawing inspiration has long been a cornerstone of artistic development. Renaissance painters emulated their predecessors. Manga artists pay tribute to iconic paneling styles. Even Walt Disney’s early animations were inspired by silent-era cartoons.

Inspiration can be visual, thematic, or stylistic. A cartoonist might adopt the exaggerated facial expressions of Sergio Aragonés, the narrative density of Art Spiegelman, or the surreal humor of Gary Larson. These influences blend into an artist’s personal voice, creating something new from something old.

But here’s the key: Inspiration transforms. It absorbs the essence without imitating the specifics.

2. What Is Referencing in Art?

Referencing involves using external images or materials to inform an artwork. Common references include photographs, movie stills, sculptures, and real-life models. Artists often use references for anatomy, lighting, perspective, architecture, and clothing.

Using references is not only acceptable but encouraged—especially for accuracy and learning. In fact, art education frequently begins with “master studies,” where students replicate famous works to understand composition, technique, and form. As long as the result is a reinterpretation, reference use is part of the creative process.

However, ethical referencing requires transformation. If the final piece looks substantially similar to the original source, then it moves from inspiration into the realm of copying.

3. When Does Referencing Become Copying?

Copying occurs when the final work mimics the source material too closely, either in composition, pose, detail, or subject matter. Here are a few red flags that suggest copying:

- The artist traces or overlays a reference.

- The new work mimics exact lighting, pose, or angles with little variation.

- Details such as clothing, expression, and background are replicated.

- The viewer could reasonably mistake the new piece for the original.

A common mistake among beginners is relying too heavily on a single reference without altering it significantly. While tracing can be a private learning tool, publishing traced or overly derivative work without attribution or transformation is both ethically and legally problematic.

4. Copyright Law and Visual Art

Copyright is a legal framework designed to protect original works of authorship, including paintings, drawings, comics, and photographs. In most countries, including the U.S., U.K., and those governed by the Berne Convention, copyright automatically exists the moment a work is created in a tangible form.

Here are key principles:

- Originality: The work must be independently created and show some level of creativity.

- Fixation: The work must be recorded or expressed in a tangible medium.

- Automatic Protection: Registration is not required, though it helps in legal disputes.

Importantly, ideas are not protected—only the expression of ideas. For instance, the idea of a superhero flying through space is not copyrighted, but the specific illustration of that hero with a unique costume, pose, and setting may be.

5. What Constitutes Copyright Infringement?

An artist may be guilty of copyright infringement if they:

- Reproduce a copyrighted image without permission.

- Create a derivative work that closely resembles the original.

- Sell or distribute works based on copyrighted content.

- Use copyrighted material for commercial gain without licensing it.

This applies to drawings made from photographs, stills from films, or another artist’s work. Even if you “draw it by hand,” copyright infringement can still occur if the work is substantially similar.

In landmark cases such as Rogers v. Koons, artist Jeff Koons was found guilty of infringement for copying a photograph too closely in a sculpture, despite changing the medium. The court ruled that the “total concept and feel” was copied.

6. Fair Use: A Limited Defense

In the U.S., the doctrine of fair use provides limited exceptions to copyright infringement. Fair use allows for reproduction without permission for:

- Criticism or commentary

- Parody

- News reporting

- Educational use

Courts evaluate four factors to determine fair use:

- Purpose and character (commercial vs. non-commercial, transformative nature)

- Nature of the copyrighted work

- Amount and substantiality of the portion used

- Effect on the market value of the original

A comic strip that satirizes a popular movie scene may qualify as fair use, particularly if it transforms the original into a new, critical commentary. But simply redrawing a photo with minimal change rarely qualifies.

7. Case Studies: Where Artists Crossed the Line

Case 1: Shepard Fairey’s Obama “Hope” Poster Based on an AP photograph, the iconic poster led to a legal battle over usage rights. Although Fairey argued it was transformative, the court disagreed, especially after discovering he tried to cover up his use of the original photo.

Case 2: Richard Prince and Instagram Art Prince reproduced others’ Instagram photos, added comments, and exhibited them. While hailed by some as postmodern commentary, several photographers sued him for infringement. The lawsuits raised critical questions about transformative use in the digital age.

8. Ethical Considerations: Respecting Fellow Artists

Even if a copied work skirts legal boundaries, it may still violate ethical norms within the art community. Copying another artist’s work without credit, permission, or significant alteration erodes trust and undermines originality.

Respect for your peers requires:

- Crediting source material when directly inspired

- Asking for permission when in doubt

- Avoiding commercial exploitation of someone else’s intellectual property

Cartoonists, especially, walk a fine line between parody and plagiarism. Referencing cultural icons is common, but it must be done with awareness and originality.

9. Best Practices for Using Reference Images

To avoid legal and ethical pitfalls, here are some best practices:

- Use multiple references: Combine elements from various sources to create something new.

- Transform the reference: Change the pose, expression, angle, or setting.

- Use royalty-free or Creative Commons images: These are safe for reference and often free to use.

- Ask for permission: Especially if you’re using work from another living artist.

- Create your own reference material: Photograph models, build 3D mockups, or sketch from life.

10. Tools for Artists: Where to Find Legal References

Several platforms provide legal and high-quality reference material for artists:

- Unsplash and Pexels: Free stock photography with generous usage rights

- Pixabay: Royalty-free images, vectors, and illustrations

- Line of Action, QuickPoses: Pose references for figure drawing

- Posemaniacs, SketchDaily, PhotoReference for Comic Artists: Artist-centric resources

Additionally, museums and libraries like The MET and The British Library offer open-access collections for public use.

The age of Instagram and TikTok has introduced new complexities. Artists frequently post time-lapse videos, mashups, and reimaginings. While remix culture fosters creativity, it also blurs legal boundaries.

For emerging artists:

- Avoid copying viral artwork without permission.

- Don’t assume “everyone is doing it” means it’s safe.

- Respect watermarking and attribution guidelines.

12. When You’ve Been Copied: What Can You Do?

If your work has been copied:

- Reach out privately: Most cases resolve through polite requests.

- Issue a DMCA takedown: Platforms like Instagram, Etsy, or YouTube allow this.

- Document the infringement: Save screenshots and dates.

- Consult a lawyer: Especially if the copy is being sold or exhibited commercially.

For cartoonists published in syndicates or magazines, contracts often grant the publisher copyright. Understand your rights and whether the publisher will assist in enforcement.

Inspiration vs. Copying: Creativity, Not Copying

Art thrives on influence. But creativity means pushing past replication into innovation. Cartoonists, illustrators, and comic creators wield incredible power to shape culture and consciousness. With that power comes responsibility—to be ethical, respectful, and original.

Using references is a valuable and legitimate part of the artistic process—but transforming those references into something unmistakably your own is where true artistry begins. In an era where digital footprints are easily traceable and copyright law is more accessible than ever, the safest path forward is one paved by authenticity.

So, the next time you find yourself staring at a reference photo, ask: Am I inspired—or am I copying?

Because that one question might make all the difference.