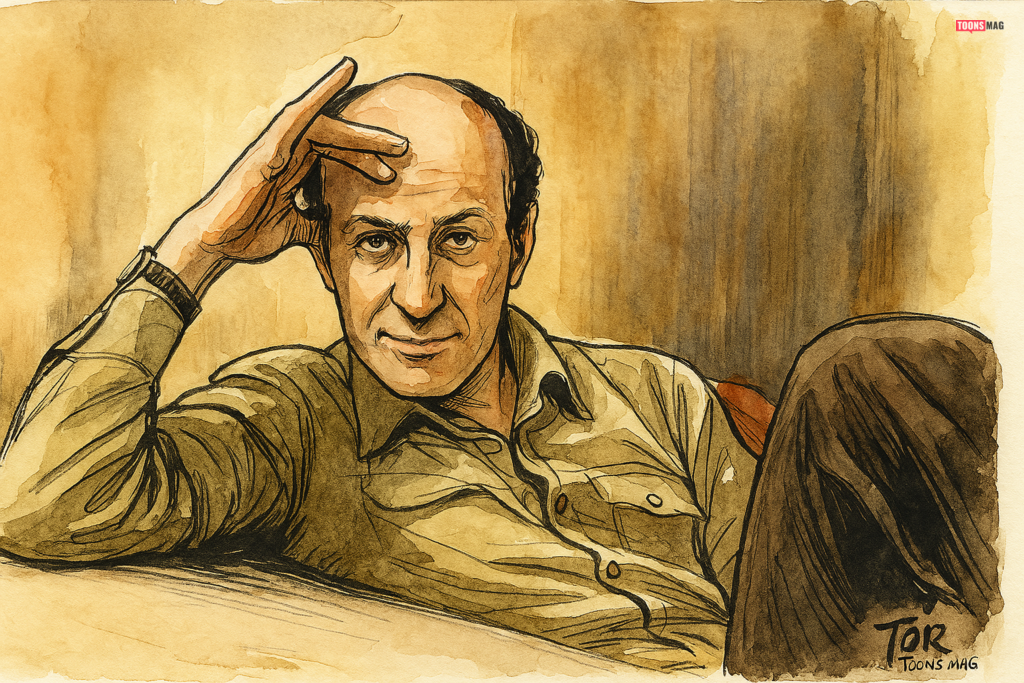

Harvey Kurtzman (/ˈkɜːrtsmən/; October 3, 1924 – February 21, 1993) was an American cartoonist, writer, and editor whose groundbreaking work transformed the landscape of comics and satire in the 20th century. He is best known as the creator and original editor of Mad magazine, which he helmed from 1952 to 1956, pioneering a new form of comic book storytelling rooted in biting humor, cultural parody, and social critique. From 1962 to 1988, he co-created and wrote Little Annie Fanny for Playboy, one of the most lavishly produced comic strips of its time.

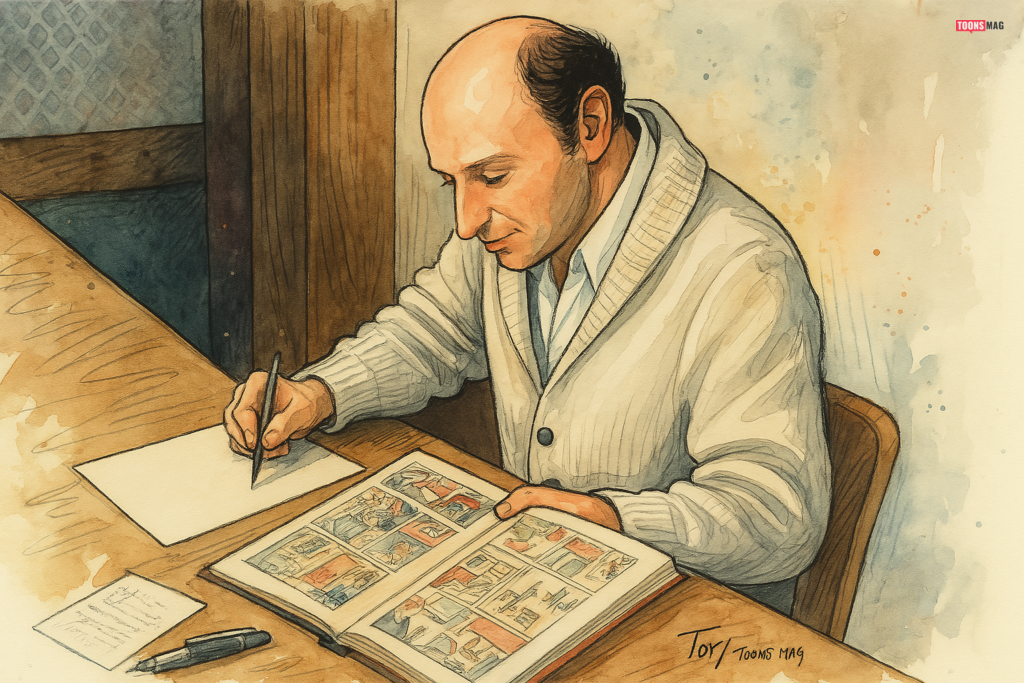

Revered for his meticulous attention to narrative detail, Kurtzman often operated as a comic auteur, crafting detailed layouts for his collaborators to follow precisely—an approach that elevated comic books to a more cinematic and literary art form. His influence reached far beyond the world of comics, inspiring generations of satirists, filmmakers, and humorists. Throughout his career, Kurtzman was recognized for blending sharp wit, intellectual commentary, and visual storytelling, leaving an indelible mark on American pop culture and earning a place among the most influential cartoonists of all time.

Harvey Kurtzman

| Name | Harvey Kurtzman |

|---|---|

| Born | October 3, 1924, Brooklyn, New York City, U.S. |

| Died | February 21, 1993 (aged 68), Mount Vernon, New York, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Cartoonist, editor, writer, illustrator |

| Notable works | MAD Magazine, Little Annie Fanny, Hey Look!, Jungle Book |

| Collaborators | Will Elder, Jack Davis, Wally Wood, Al Jaffee, Terry Gilliam |

| Awards | Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame (1989), Harvey Award (named in his honor, 1988), Angoulême Grand Prix (1995, posthumous) |

Biography

Early Life and Education

Harvey Kurtzman was born on October 3, 1924, in Brooklyn, New York City, to Ukrainian-Jewish immigrants David Kurtzman and Edith Sherman. His early life was marked by both adversity and creativity. When Harvey was just four years old, his father died of a bleeding ulcer, leaving the family in financial hardship. As a result, Harvey and his older brother Zachary were briefly placed in an orphanage until their mother was able to support them again. She eventually remarried Abraham Perkes, a brass engraver and dedicated trade unionist. Perkes had a deep respect for craftsmanship and the arts and often took Harvey along to his workplace, exposing him to visual design and engraving tools.

This had a formative influence on the young Kurtzman, nurturing his creative ambitions and encouraging him to view himself as a professional artist from a young age.

During the Great Depression, the family moved to the Bronx, where Kurtzman’s talent began to flourish. He started drawing comic strips on sidewalks with chalk, attracting crowds of neighborhood children and passersby. His work caught the attention of teachers and local artists, who recognized his unique sense of humor and visual storytelling. He was accepted into The High School of Music & Art, one of New York’s premier institutions for young artists. There, he formed lasting friendships with future comic legends Will Elder, Al Jaffee, and John Severin. He distinguished himself by winning several prestigious art contests, including the Wanamaker Art Contest, which helped secure him a scholarship to Cooper Union.

At Cooper Union, Kurtzman was exposed to classical art education, but he found the curriculum too rigid and academic for his growing interest in comic books and satire. Within a year, he made the bold decision to leave the school and fully immerse himself in the burgeoning comic book industry. During this time, he devoured the work of newspaper strip artists like Milt Caniff and Alex Raymond, and especially idolized Will Eisner’s The Spirit, whose storytelling and design principles would have a profound influence on his later work. It was here that his lifelong love affair with comics—particularly satire, parody, and socio-political commentary—began to take full shape.

Early Career (1940s)

Kurtzman began his professional career in 1942 at Louis Ferstadt’s studio, contributing to Classic Comics, Four Favorites, and other war-era books. His early assignments included background work and penciling, but he quickly began making his mark with inventive layouts and an intuitive sense for timing and visual rhythm. He absorbed practical lessons in mass-market storytelling from Ferstadt and others, lessons that would influence his later work on educational and satirical comics.

During World War II, Kurtzman was drafted into the U.S. Army and assigned to infantry training. While stationed at various military bases across the southern United States, he put his cartooning skills to use by illustrating instruction manuals, drawing safety posters, and contributing gag panels to base newspapers. These experiences not only improved his draftsmanship and speed but also allowed him to observe military life with a critical and often humorous eye—an eye that would later shape his anti-war narratives in Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat.

After returning to civilian life, he joined forces with fellow artists Will Elder and Charles Stern to form the Charles William Harvey Studio. The trio initially struggled to find steady work, but eventually began to freelance for various publishers, including Timely Comics (later Marvel). It was during this period that Kurtzman developed his signature strip Hey Look!, producing 150 one-page gags between 1946 and 1949. Though brief, each page showcased an explosive sense of timing, compressed storytelling, and screwball humor that would become hallmarks of his mature style. The strip has since been hailed as a mini-masterclass in comedic visual pacing and layout.

In 1948, Kurtzman married Adele Hasan, a fellow employee at Timely Comics. Their partnership extended beyond marriage, as Adele supported Harvey’s demanding creative career and later managed his business affairs and charitable endeavors. Together, they raised four children and remained deeply involved in the comic arts community, frequently opening their home to fellow cartoonists and emerging talents.

EC Comics and the Birth of MAD (1950–1956)

In 1950, Kurtzman joined EC Comics and made his mark writing and editing Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat. These anti-war comics were revolutionary for their humanistic and historically accurate portrayals of war, told through exhaustive research and emotionally compelling layouts. His collaborative approach—providing detailed layouts to artists like John Severin and Alex Toth—became legendary.

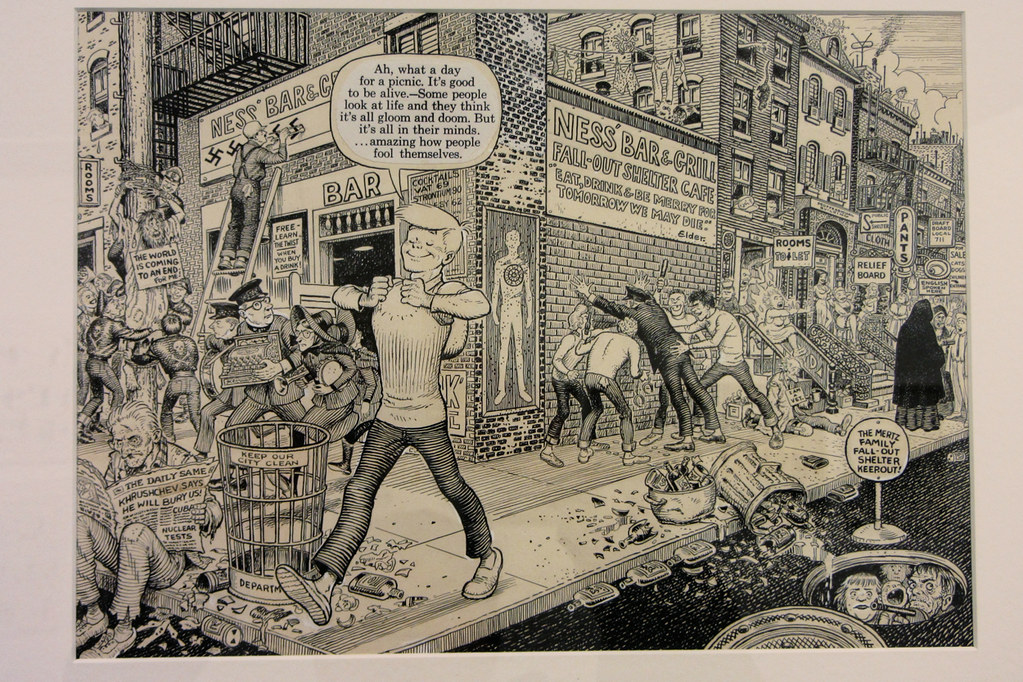

In 1952, EC publisher William Gaines gave Kurtzman the green light to start a humor comic: MAD. With artistic collaborators like Will Elder, Wally Wood, and Jack Davis, MAD revolutionized satire and pop culture critique. MAD‘s parody of Superman (Superduperman) was a turning point that made the magazine a cultural phenomenon.

In 1955, MAD transitioned from comic book to magazine format, providing more editorial freedom and legal protection for parody. However, a dispute over ownership led to Kurtzman’s departure in 1956, a decision widely viewed as the biggest loss for EC Comics.

Trump, Humbug, and Jungle Book (1956–1959)

Hugh Hefner invited Kurtzman to create a high-quality humor magazine called Trump, envisioning it as a sophisticated satirical publication that could stand alongside Playboy. Launched in 1957, Trump featured lavish full-color illustrations, top-tier contributors including Will Elder, Al Jaffee, Jack Davis, and Arnold Roth, and witty articles penned by literary talents like Roger Price and Mel Brooks. Despite a promising debut and favorable reception, financial strain within Hefner’s growing publishing empire led to the magazine’s abrupt cancellation after only two issues. The shutdown was a bitter disappointment for Kurtzman, who regarded Trump as his closest attempt at a “perfect humor magazine.”

Undeterred, Kurtzman and a group of trusted collaborators, including Elder, Jaffee, and Roth, pooled their resources to launch Humbug later in 1957. Unlike its glossy predecessor, Humbug was printed in black and white and sold at a budget-friendly price. It emphasized artistic freedom, topical satire, and an eclectic, intellectual humor that set it apart from mainstream publications. Despite its creative brilliance and devoted cult following, Humbug struggled with poor distribution, low visibility on newsstands, and a limited marketing budget. After 11 issues, the magazine folded in 1958, leaving a lasting impression on those who appreciated its wit and artistic ambition.

In 1959, Kurtzman shifted gears and authored Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book, published by Ballantine Books. It was the first mass-market paperback comprised entirely of original comic content, breaking new ground in the format and paving the way for what would later be recognized as the graphic novel. The stories in Jungle Book combined sharp social commentary, absurdist humor, and psychological depth, addressing themes such as suburban conformity, military bureaucracy, and racial prejudice. Although it failed commercially at the time, the book has since gained recognition as one of Kurtzman’s most personal and artistically rich works—a landmark in adult comics storytelling.

Help! Magazine and Little Annie Fanny (1960–1988)

From 1960 to 1965, Kurtzman edited Help!, a budget humor magazine published by James Warren. Despite its modest funding, Help! was artistically ambitious and culturally influential. It became a breeding ground for emerging talents, including underground comix legends Robert Crumb and Gilbert Shelton, as well as British cartoonist Terry Gilliam, who would later join Monty Python. Feminist icon Gloria Steinem also contributed photo comics and editorial work, making Help! one of the few satirical magazines of the time to feature female voices. The magazine was known for pushing boundaries with its mix of fumetti (photo comics), spoof advertisements, and biting political satire.

One of its most controversial pieces, “Goodman Goes Playboy,” parodied the clean-cut world of Archie Comics and ended in a lawsuit—but also impressed Hugh Hefner, reigniting a professional relationship that would define the next chapter of Kurtzman’s career.

That chapter began with Little Annie Fanny, the lavish, full-color comic strip that debuted in Playboy in 1962. Co-created with Will Elder, the strip combined Hefner’s demand for sex appeal with Kurtzman’s desire for satirical commentary. It parodied everything from pop culture and politics to Hollywood and advertising, often lampooning real celebrities with razor-sharp caricature and social critique. The strip was groundbreaking not just for its risqué content but also for its format—Little Annie Fanny was the first fully painted comic to appear in a mainstream American magazine.

Each installment was a feat of visual storytelling: Kurtzman storyboarded every panel in detail, guided the narrative tone, and meticulously collaborated with Elder, who rendered the final art with oil-based paints to achieve a polished, painterly aesthetic.

Despite mixed critical reception—some praised it as genius, others dismissed it as pandering—Little Annie Fanny proved to be a commercial success and a steady source of income for Kurtzman, sustaining his career for over two decades while keeping his creative spirit alive in an ever-evolving media landscape.

Teaching, Recognition, and Final Years (1970–1993)

In 1973, Kurtzman joined the School of Visual Arts in New York, teaching “Satirical Cartooning” for two decades. He mentored future legends like Art Spiegelman and Drew Friedman. He also co-founded Kar-Tünz, an annual anthology showcasing student work.

During the 1980s, Kurtzman’s legacy gained broader appreciation. He oversaw deluxe reprints of his early works, was inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame (1989), and had five entries on The Comics Journal’s Top 100 Comics of the 20th Century. In 1988, the Harvey Awards were established in his name.

Though he returned to MAD briefly in the late 1980s and published Harvey Kurtzman’s Strange Adventures in 1990, his health began to decline. Suffering from Parkinson’s and colon cancer, he passed away on February 21, 1993. He was mourned as one of cartooning’s greatest innovators.

Selected Works

- Hey Look! (Timely Comics, 1946–1949)

- Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat (EC Comics, 1950–1954)

- MAD #1–23 (EC Comics, 1952–1955)

- Trump (Playboy, 1957)

- Humbug (Self-published, 1957–1958)

- Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book (Ballantine Books, 1959)

- Help! (Warren Publishing, 1960–1965)

- Little Annie Fanny (Playboy, 1962–1988)

- Strange Adventures (DC Comics, 1990)

Awards and Honors

- 1988: Harvey Awards established in his name

- 1989: Inducted into the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame

- 1993: Posthumous tributes in The New Yorker, Time, and global comics community

- Five entries on The Comics Journal’s Top 100 Comics of the 20th Century

Further Reading

- The Art of Harvey Kurtzman: The Mad Genius of Comics by Denis Kitchen & Paul Buhle (2009)

- Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created MAD by Bill Schelly (2015)

- Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book: Essential Kurtzman Vol. 1 (Dark Horse, 2014)

Legacy and Influence

Harvey Kurtzman’s influence on comics, satire, and American pop culture is immeasurable and enduring. A trailblazer who rewrote the rules of visual storytelling, Kurtzman helped define what modern humor could be—sharp, intelligent, fearless, and unafraid to challenge authority or convention. Through groundbreaking works like MAD Magazine, he set the tone for political and cultural satire in comics, inspiring countless writers, illustrators, and comedians. His irreverent yet thoughtful style paved the way for the underground comix revolution of the 1960s and 70s, which reshaped the landscape of independent publishing.

Terry Gilliam referred to him as a godfather of Monty Python; Art Spiegelman hailed him as the “cartoonist’s cartoonist”—an artist’s artist whose fingerprints can be found in everything from editorial cartoons to Saturday Night Live sketches. Kurtzman’s legacy reverberates through the Harvey Awards, MAD Magazine, underground comix, and the very structure of how satire is approached in television, film, and digital media.

What set Kurtzman apart was not just his humor but his painstaking craftsmanship. His meticulous layouts, relentless dedication to narrative clarity, and demand for artistic precision often placed him in the role of an auteur—a director-like figure in the comics world. He expected his collaborators to follow his vision closely, elevating comics to a form of visual literature. His works—including Jungle Book, Hey Look!, Two-Fisted Tales, and Goodman Beaver—are more than classics; they are case studies in how to combine biting social commentary with masterful storytelling. These works remain foundational texts for students of comics, satire, and sequential art.