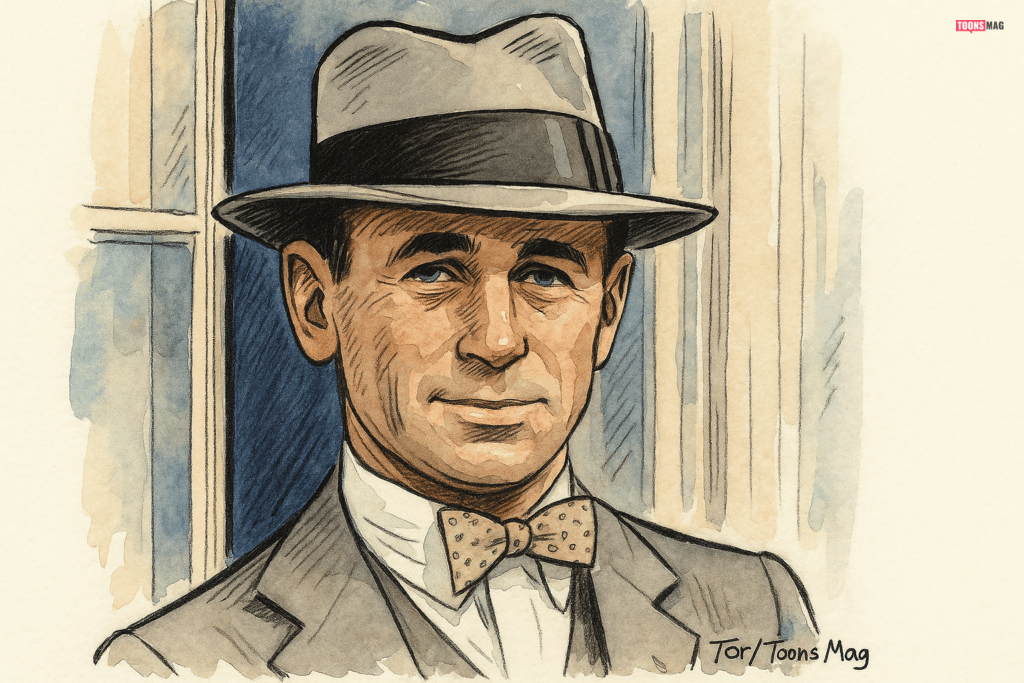

Reuben Garrett Lucius Goldberg (July 4, 1883 – December 7, 1970), famously known as Rube Goldberg, was an American cartoonist, inventor, sculptor, author, and engineer. He is best known for his iconic cartoons illustrating wildly complicated machines designed to perform simple tasks in the most convoluted ways imaginable. These creations became so culturally significant that the term “Rube Goldberg machine” is now universally recognized to describe any overly complex contraption meant to achieve an otherwise simple result.

Goldberg was not only a creative genius but also a sharp satirist who used humor, irony, and mechanical absurdity to critique modern life. His works transcended the boundaries of cartooning, influencing film, design, engineering, and even popular culture on a global scale.

Infobox: Rube Goldberg

| Full Name | Reuben Garrett Lucius Goldberg |

|---|---|

| Known As | Rube Goldberg |

| Born | July 4, 1883 |

| Birthplace | San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | December 7, 1970 |

| Death Place | New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Resting Place | Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Hawthorne, NY |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of California, Berkeley (Engineering) |

| Occupations | Cartoonist, Inventor, Sculptor, Author, Engineer |

| Known For | Rube Goldberg Machines, Satirical Cartoons |

| Spouse | Irma Seeman (m. 1916) |

| Children | 2 (including George W. George) |

| Awards | Pulitzer Prize (1948), Reuben Award (1967), Gold T-Square Award (1955), Banshees’ Silver Lady Award (1959) |

Early Life and Education

Goldberg was born on July 4, 1883, in San Francisco, California, to Jewish parents Max and Hannah Goldberg. He was the third of seven children, although only four survived into adulthood. His father, Max, served as a respected police and fire commissioner, deeply invested in civic leadership and determined to instill strong values of discipline and education in his children. Max hoped his son would pursue a respectable and secure career, ideally in the field of engineering or law.

Despite these intentions, young Rube exhibited an extraordinary aptitude for drawing from the age of four. He was endlessly curious and imaginative, often observed scribbling on scraps of paper and mimicking newspaper illustrations. His only structured art training came from a local sign painter, but his style developed through constant experimentation and sheer observational brilliance.

Goldberg’s early childhood was shaped by both tragedy and wonder. The loss of three siblings in infancy deeply affected the family and left Goldberg with an acute awareness of life’s fragility. He often retreated into his own world of fantastical drawings and humorous illustrations as a form of solace and self-expression. He displayed a fascination with machines, gadgets, and mechanical systems early on, and he delighted in disassembling household items to understand their workings—much to his parents’ dismay.

Pushed by his father to follow a more practical path, Goldberg enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1901, studying mining and civil engineering. His time at Berkeley proved to be transformative—not only did he gain a technical foundation that would later define his cartooning style, but he also came into contact with influential mentors like Professor Frederick Slate, whose humorous and challenging engineering assignments made a lasting impression. Goldberg graduated in 1904 with an engineering degree, and was soon hired by San Francisco’s Water and Sewers Department.

However, his government post left him creatively stifled. He found the bureaucratic environment and repetitive nature of his duties uninspiring. After just six months on the job, Goldberg made the pivotal decision to abandon engineering and pursue a career as a cartoonist. He returned to his lifelong passion for drawing, setting his sights on the dynamic world of newspaper publishing—a decision that would not only define his career but also shape American visual culture for generations to come.

Career Breakthrough and Invention Cartoons

Goldberg’s cartooning career began in earnest at the San Francisco Chronicle and later at the San Francisco Bulletin, where his knack for visual humor and storytelling caught public attention. His early work demonstrated a unique ability to merge witty satire with captivating artwork, appealing to a growing readership in the rapidly expanding newspaper industry. In 1907, he made a bold move to New York City, then the heart of American publishing, where he joined the New York Evening Mail as a sports cartoonist. This transition marked a crucial turning point in his career, exposing him to a national audience and the bustling artistic circles of the East Coast.

His breakthrough came in 1908 with the debut of Foolish Questions, a comic strip that poked fun at the obvious and redundant queries people often ask. The strip became a cultural phenomenon, widely syndicated and adapted into merchandise and games. Building on its success, Goldberg introduced additional strips such as Mike and Ike (They Look Alike), which humorously explored the antics of identical twins, and Boob McNutt, which followed the misadventures of a well-meaning but clueless protagonist. These characters became household names and were instrumental in establishing Goldberg as a leading figure in American humor.

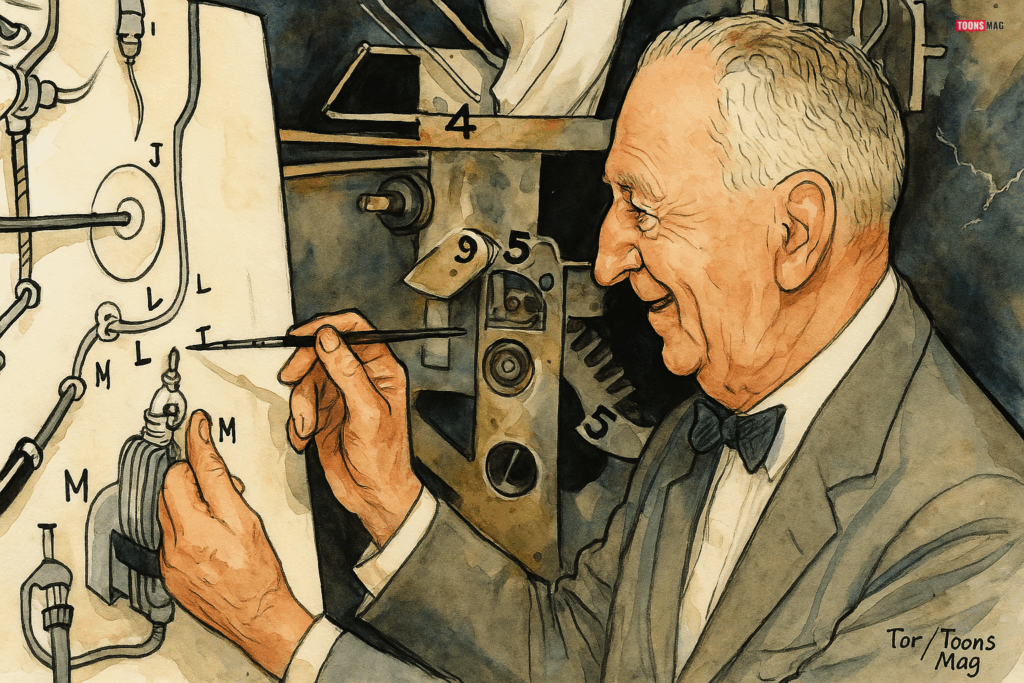

Goldberg’s invention cartoons began around 1912, inspired by both his engineering background and a growing skepticism of the increasingly convoluted systems in modern life. His work in this genre truly blossomed with The Inventions of Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts, published in Collier’s Weekly from 1929 to 1931. These comically overengineered contraptions used an absurd sequence of levers, pulleys, animals, and household objects to perform simple tasks—like wiping a chin, setting an alarm, or swatting a fly. Each machine was accompanied by precise labels and instructions, parodying the technical diagrams of real engineering blueprints.

Goldberg’s invention cartoons served as brilliant satire on the overly complex mechanisms of bureaucracy, industry, and modern society. His machines became metaphors for inefficiency and the absurdity of progress, resonating deeply during an era of rapid industrialization. What made them particularly compelling was their mechanical plausibility—his engineering training enabled him to construct contraptions that, while ridiculous, theoretically could function. This blend of technical realism and comic absurdity became Goldberg’s hallmark and secured his lasting legacy in both art and engineering circles.

Accomplishments and Honors

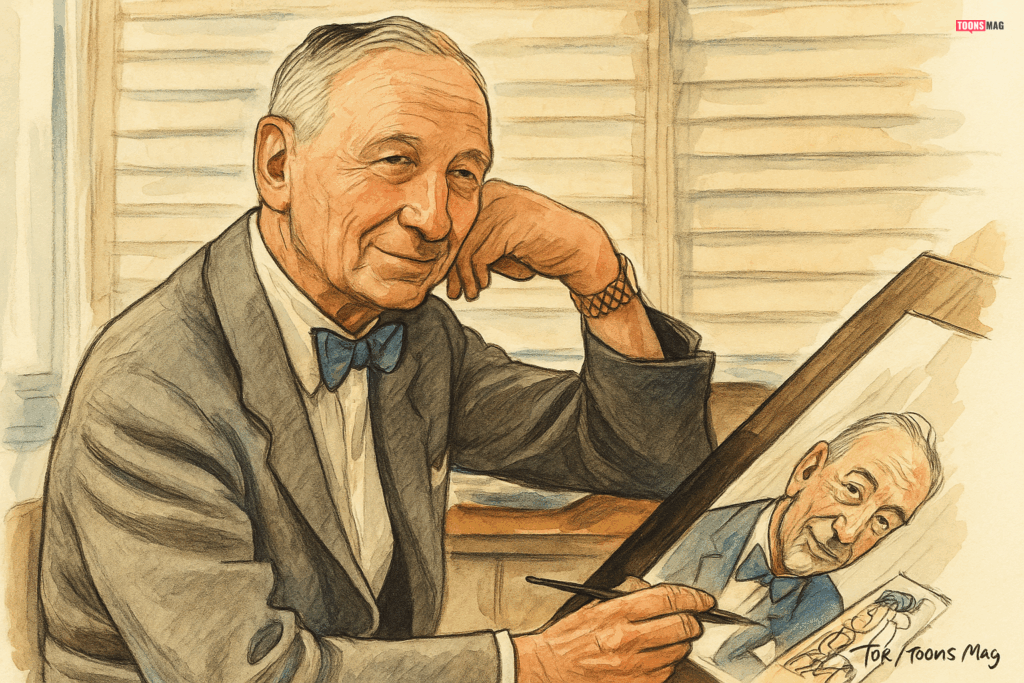

Throughout his prolific career, Goldberg created over 50,000 cartoons, making him one of the most productive artists of his era. He was also an accomplished author, writing humorous essays and illustrating books that expanded his influence beyond newspapers.

Goldberg’s sharp political cartoons earned him the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for a cartoon titled “Peace Today,” which addressed the threat of atomic war. He was not afraid to challenge government policy, public ignorance, or social hypocrisy through his biting illustrations.

Goldberg was also a founding member and the first president of the National Cartoonists Society, which named its annual Reuben Award after him. He won the award himself in 1967.

Additional accolades include:

- Gold T-Square Award (1955)

- Banshees’ Silver Lady Award (1959)

- Featured in Comic Strip Classics U.S. postage stamp series (1995)

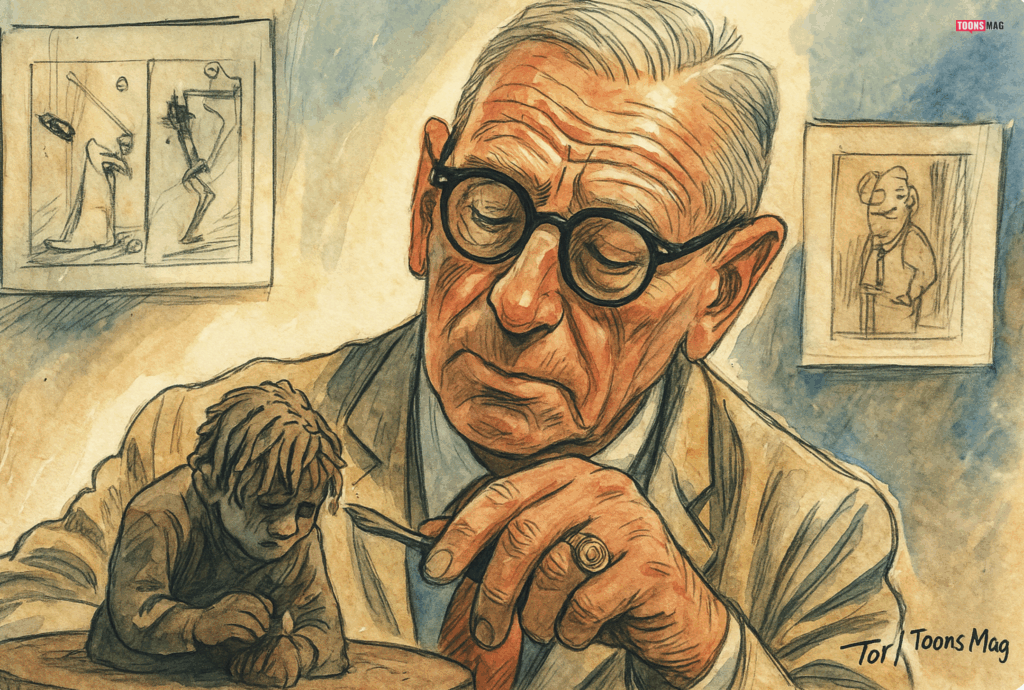

In the 1960s, Goldberg transitioned into sculpture, mainly working on busts, expanding his artistic scope in his final years. He retired from professional cartooning in 1963 and passed away in 1970 at the age of 87, leaving behind a rich legacy of innovation and satire.

Personal Life

Goldberg married Irma Seeman in 1916, and they settled in New York City at 98 Central Park West, an upscale address on the Upper West Side, reflecting both Goldberg’s rising prominence and his desire for cultural immersion in the heart of the city. The couple had two sons: Thomas and George, both of whom were raised in a household filled with humor, intellect, and creative inspiration. Goldberg often entertained his children with humorous stories and sketching sessions, and their home became a gathering place for artists, writers, and cultural figures of the time.

As World War II brought increased antisemitic sentiment, especially toward high-profile figures, Goldberg became increasingly concerned about the potential impact of his political cartoons on his children. Wanting to shield them from prejudice and to avoid any professional or social disadvantage tied to his controversial work, Goldberg urged his sons to change their surnames. Both adopted the surname George, derived from the given name of one of the sons, as a means of preserving familial unity while adapting to a changing and often hostile social environment.

Goldberg was known to be a private but humorous man, who cherished quiet moments with his family amid his prolific professional life. He was deeply devoted to his wife and children, often involving them in his creative processes and sharing his satirical views in daily conversation. Loyal to his friends and generous with his time, he was also a mentor to aspiring cartoonists and artists. Despite his fame and acclaim, Goldberg maintained a modest lifestyle, preferring simple pleasures like sketching, sculpting, and engaging in long discussions about philosophy and politics. He continued to produce ideas, concepts, and doodles well into retirement, often remarking that the world was always offering something new and absurd to draw inspiration from.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

Rube Goldberg’s name has become synonymous with unnecessary complexity, often embodying the intersection of creativity, satire, and exaggerated problem-solving. The term “Rube Goldberg machine” is now a fixture in everyday language, used across disciplines ranging from physics and engineering to economics and political science to describe overly elaborate or inefficient processes designed to achieve a simple result. His name frequently appears in academic research, newspaper editorials, and popular media to illustrate concepts such as bureaucratic inefficiency, design overkill, or technological absurdity.

His influence extended far beyond the United States and became a part of international cartooning lexicon. In the UK, cartoonist Heath Robinson was recognized as a kindred spirit, known for his own eccentric machines that solved trivial problems through hilariously indirect methods. So closely aligned were the two in their visual humor and mechanical absurdity that “Heath Robinson” became the British equivalent of “Rube Goldberg.”

In Denmark, artist and humorist Storm P. (Robert Storm Petersen) created contraptions with a similar spirit of whimsy and satire, deeply resonating with Danish audiences. To this day, overly complicated contraptions are known as “Storm P. machines” in Danish culture. Similar cultural counterparts have emerged in other countries as well, with inventors and artists referencing Goldberg’s approach to satirical engineering. From Japan’s TV game shows to Germany’s kinetic art installations, Goldberg’s influence is a global phenomenon that continues to entertain, challenge, and inspire inventors, artists, and everyday problem solvers alike.

Rube Goldberg in Popular Culture

Goldberg’s work has been referenced or parodied in hundreds of films, television shows, and comics:

- Wrote Soup to Nuts (1930), the first film to feature The Three Stooges.

- His whimsical machines were mirrored in films such as Back to the Future, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, Wallace & Gromit, Home Alone, and Edward Scissorhands.

- Appeared in episodes and educational segments of Sesame Street, The Electric Company, and iCarly.

- Music videos, including OK Go’s This Too Shall Pass, paid tribute to Goldberg’s mechanical chain reactions.

Rube Goldberg Machine Contest

In 1949, Purdue University hosted the inaugural Rube Goldberg Machine Contest, originally conceived as a spirited rivalry between two engineering fraternities. The goal was to honor Goldberg’s legacy by challenging participants to design overly elaborate machines to perform mundane tasks. Initially a niche event, the contest gradually expanded and gained national traction, thanks in part to increasing interest in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) education.

By 1989, the contest evolved into a national competition, attracting university teams from across the country. Its appeal grew even further with the introduction of a high school division in 1996, opening doors for younger students to engage in hands-on engineering and creative problem-solving. The tasks often assigned—such as zipping a zipper, hammering a nail, or watering a plant—must be accomplished using a minimum of twenty steps and can involve as many as seventy-five, all executed in true Goldberg fashion: whimsical, complex, and spectacular.

Today, the contest is operated by Rube Goldberg Inc., a non-profit organization founded by his son George W. George and currently managed by his granddaughter Jennifer George. Under her guidance, the contest has embraced new educational standards and integrated digital platforms, further expanding its accessibility to students in rural and underserved areas. The competition not only celebrates Goldberg’s humorous and inventive spirit but also promotes vital skills like teamwork, critical thinking, and mechanical reasoning.

It has become a beloved annual event in the U.S., with participants often showcasing their machines through public exhibitions, national media, and online platforms. In doing so, the contest perpetuates Goldberg’s enduring message—that learning and creativity should always be fun, messy, and full of imagination.

Games and Media Inspired by Goldberg

- Classic board game Mouse Trap was directly inspired by Goldberg’s inventions.

- Popular video games such as The Incredible Machine, Crazy Machines, and Rube Works (2013) recreate his puzzle-solving spirit.

- His cartoon Foolish Questions inspired a card game in 1909 that remained popular through the 1930s.

Posthumous Recognition

- Inducted into various halls of fame and featured in major museum retrospectives

- His name used in political discourse, including a famous reference by Justice Antonin Scalia in 1998

- Exhibitions of his work continue to draw large audiences around the world

Rube Goldberg remains one of the most imaginative and influential figures in American popular culture. More than a cartoonist, he was a social commentator, inventor of cultural memes, and a pioneer in visual storytelling. His absurdly ingenious machines, incisive political cartoons, and creative vision continue to entertain and educate generations of artists, engineers, designers, and thinkers. Goldberg’s ability to turn complexity into comedy—while making us think critically about technology, systems, and human nature—secures his place among the true legends of American art and humor.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!